Carboxylic acids produced by anaerobic digestion:sugarcane and cassava

Warde Antonieta da Fonseca-Zang2

Regina Célia Bueno da Fonseca3

Wilson Mozena Leandro4

Cláudia Adriana Bueno da Fonseca5

Alex Mota dos Santos6

Abstract

This research investigated the production of carboxylic acids (CA) by anaerobic digestion (AD) using organic agro-industrial waste from Brazil. Two experimental routes were tested: Route A for biogas production with active archaea and Route B for CA production with inhibited archaea, using different pH conditions to suppress methanogenesis. The residues analyzed were sugarcane filter cake and cassava peel processing residues, with bovine manure as inoculum. The concentration of short-chain carboxylic acids (SCCA) was evaluated over 21 days using gas chromatography with flame ionization detection (FID). The most significant values were observed for acetic acid (43%) and butyric acid (40%) contents, increasing on day 4 of the experiment from route A to route B in the case of acetic acid from 51 mg/gMSO to 294 mg/gMSO, and in the case of butyric acid from 15 mg/gMSO to 197 mg/gMSO, respectively, when using sugarcane filter cake from the Brazilian sugar-energy sector. This suggests that sugarcane filter cake may be an effective substrate due to its rich organic content and favorable fermentation characteristics. On the other hand, CA production from cassava peel was low (0%) under the experimental conditions tested for acid contents, probably due to its limited nutritional composition. These results highlight the potential of sugarcane bagasse as a promising raw material for the sustainable production of AC through AD with methanogenesis inhibition, contributing to the development of renewable energies and bioproducts.

Keywords: Biomass; biogas; chemical platform; organic agro-industrial waste.

Ácidos carboxílicos produzidos por digestão anaeróbica:cana-de-açúcar e mandioca

Resumo

Esta pesquisa investigou a produção de ácidos carboxílicos (AC) por digestão anaeróbica (DA) utilizando resíduos agroindustriais orgânicos do Brasil. Duas rotas experimentais foram testadas: Rota A para produção de biogás com arqueas ativas e Rota B para produção de AC com arqueas inibidas, utilizando diferentes condições de pH para suprimir a metanogênese. Os resíduos analisados Foram torta de filtro de cana-de-açúcar e resíduos do processamento de casca de mandioca, com esterco bovino como inóculo. A concentração de ácidos carboxílicos de cadeia curta (ACCC) foi avaliada ao longo de 21 dias usando cromatografia gasosa com detecção por ionização de chama (FID). Os valores mais significativos foram observados para os teores de ácido acético (43%) e ácido butírico (40%), aumentando no dia 4 do experimento na rota A para rota B no caso de ácido acético de 51 mg/gMSO para 294 mg/gMSO, e no caso de ácido butírico de 15 mg/gMSO para 197 mg/gMSO, respectivamente, ao utilizar torta de filtro de cana-de-açúcar do setor sucroenergético brasileiro. Isso sugere que a torta de filtro de cana-de-açúcar pode ser um substrato eficaz devido ao seu rico conteúdo orgânico e características favoráveis de fermentação. Por outro lado, a produção de AC a partir da casca de mandioca foi baixa (0%) nas condições experimentais testadas para os teores dos ácidos, provavelmente devido à sua composição nutricional limitada. Esses resultados destacam o potencial da torta de filtro de cana-de-açúcar como matéria-prima promissora para a produção sustentável de AC por meio de DA com inibição da metanogênese, contribuindo para o desenvolvimento de energias renováveis e bioprodutos.

Palavras-chave: Biomassa; biogás; plataforma química; resíduos agro-industries orgânicos.

Recebido em: 14/04/2025

Aceito em: 30/05/2025

Publicado em: 09/08/2025

1 Introduction

In recent decades, at a global level, the negative environmental impacts generated by fossil fuels have increased, especially in the face of the climate crisis, with the problem of the intensity of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions into the atmosphere (Ramio-Pujol et al, 2015; Velvizhi et al., 2023).

According to Mata-Alvarez et al. (2014), biomass rich in carbohydrates can be valorized through the process of Anaerobic Digestion (AD) of organic matter, which can generate products of great economic and environmental interest, such as gases (methane and hydrogen), solvents (ethanol, acetone and hexanol) and carboxylic acids (acetic, propionic, butyric and valeric).

The AD of organic waste is gaining prominence worldwide (Abbasi, Tauseef and Abbasi, 2012), although highly centralized policies in Asian countries such as China and South Korea have led to the rapid construction of a food waste to biogas sector (De Clercq et al., 2017; Shah and Shah, 2024). It is a process of producing energy from organic waste, which requires transformation by microorganisms under anaerobic conditions (absence of oxygen). There is a variety of organic waste (domestic, agricultural, industrial, sewage sludge and chemical) that can be processed using different methods to produce biogas, contributing to the production of renewable energy (Araújo, Feroldi and Urio, 2014; Alrefai et al., 2020; Atelge et al., 2020; Jeyakumar and Vincent, 2022; Velvizhi et al., 2023; Ren et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2025).

The decomposition of biodegradable organic waste through AD technology can also produce Short Chain Carboxylic Acids (SCCA) (Romano and Zhang, 2008; Lu et al., 2024; Cui et al., 2024).

SCCA range from C2 to C4 acids, i.e. acetic acid (C2), propionic acid (C3), lactic acid (C3) and butanoic acid (C4) which are potential renewable carbon sources that can be used to produce fuels or chemicals (Reddy, Mohan and Chang, 2018; Bhatt, Ren and Tao, 2020). They are used in a variety of applications, including polymers, food additives, pharmaceuticals and cosmetics (Formann et al., 2020; Almeida, 2021; Cui et al., 2024).

There are different ways of processing organic waste in the biorefinery concept: the sugar or fermentation platform for fuels (sugar-energy industry); the pyrolysis and synthesis gas platform, in which thermochemical systems convert biomass into synthesis gas and other products; and the carboxylate platform, where organic raw materials are converted into chemical intermediates. The carboxylate platform is a combination of biological and chemical pathways for converting organic waste into bioproducts (Agler et al., 2011).

According to Chen et al. (2008), Lee et al. (2014) and Saadoun et al. (2025) several studies can be found in the literature to guide decision-making for CA production, such as analyzing process configurations with the feasibility of the inhibition strategy in the AD process and/or variations in parameters (redox, pH, pressure, operating conditions, and others), from different raw materials, with a focus on the production of Medium-Chain Carboxylic Acids (MCCA), including CA for the production of C2-C6 acids. Vicente et al. (2025) took advantage of the outstanding traits of recombinant Yarrowia lipolytica strains to assess the conversion of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) derived from real digestates into odd-chain fatty acids (OCFA); Domingos et al. (2017) used cheese whey from dairy industries as waste; Shen et al. (2017) used tofu waste (soy-based vegetable cheese) and egg white; Cagnetta et al. (2016) used liquid agro-industrial waste, sludge from industrial effluents; Khiewwijit et al. (2015) used primary and secondary sludge from Sewage Treatment Plants (STP); Agler et al. (2011) used agro-industrial waste from corn fiber and Zhang et al. (2005) used food waste.

Sousa and Silva et al. (2020) explored the conversion of anaerobic resources from some Agro-industrial Wastewaters (AWW) using three biorefinery platforms (methane, hydrogen and carboxylic acids). AWW has excellent economic potential for the production of methane, hydrogen and carboxylic acids, but the CA platform is more economically advantageous, especially when there is the Long Carboxylic Chain Biological Process (LCBP). As a result, they showed that the AWW that obtained the highest yield in mass production of CA were pig manure and residual glycerol (Sousa and Silva et al., 2020).

Reddy et al. (2022) and Steinbusch et al. (2011) integrated AD and chain elongation technologies to produce biogas and carboxylic acids from cheese whey (CW), which is a waste product produced during cheese production. They showed how CW can produce multiple energy in the form of Short Chain Carboxylic Acids (SCCA), Medium Chain Carboxylic Acids (MCCA) and H2 using a bioenhancement strategy integrating anaerobic digestion and chain elongation technologies (Reddy et al., 2022; Steinbusch et al. 2011). The waste substrates for biofuels are agricultural and industrial waste, accounting for 47% and 34% respectively, and in terms of CA biofactories, there are still no plants in Brazil (Gustafsson et al., 2024; Ogwu et al., 2025).

Bhatt et al. (2020) provide a procedure for producing high-value SCCA from AD of US wet waste such as sludge from wastewater treatment plants, food waste, swine manure, and fats, oils and greases as an alternative to biogas. They used the AD process with methanogenesis inhibition by varying various parameters (pH, temperature, redox potential, hydraulic retention time, organic loading rate, substrate pre-treatment, co-fermentation with other wastes and waste types) that affect methanogen activity in the process to estimate carboxylic acid energy yields (Bhatt et al. 2020; Gois et al. 2025). They showed that the theoretical energy yields of the acids are equal to or exceed biogas, and the cost of these acids is competitive with those produced in chemical markets, making them economically viable for mass production.

Due to the tropical climate, AD in Brazil is widely used and investment is expected in the recovery of products such as methane and CA (Gustafsson et al., 2022; Ogwu et al., 2025). There is 811 biogas plants, of which 755 are in operation and producing energy (93%), 44 are in the implementation phase (5%), 12 are under renovation (2%) and are expected to operate again in 2022, increasing by 20% in 2020 (675 plants), indicating that the market continues to expand (CIBiogás 2022). The most widely used substrates are agricultural and industrial waste, accounting for 47% and 34% respectively. And in terms of CA biofactories, there are still no plants in Brazil (Gustafsson et al., 2022; Ogwu et al., 2025).

The purification of these compounds is a fundamental aspect for the continuity of the experiment, especially if the objective is, for example, to produce butanol from sugarcane filter cake. This is based on the DA fermentation process, which has demonstrated potential for the sustainable generation of significant amounts of butyric acid (40%).

In this context, the aim of the article is to investigate the process of AD to carboxylic chain elongation, with a view to producing CA in two routes from organic agro-industrial waste available in Brazil, in this case, sugarcane filter cake and waste from the processing of cassava peel.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Agro-industrial waste used

The waste selected is from agro-industrial plants in the state of Goiás, Brazil. The waste has favorable properties for generating biogas in the anaerobic digestion process and has significant quantities available in Brazil.

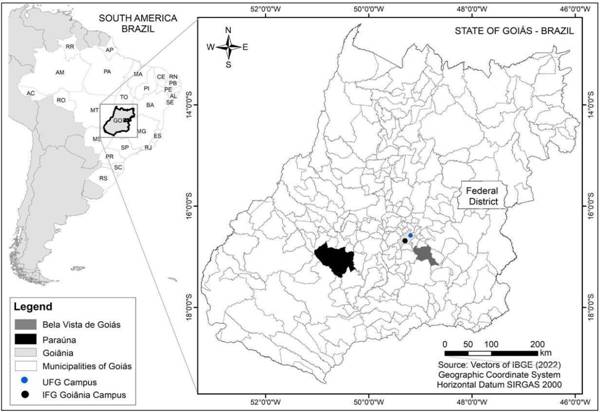

The sugar cane waste used for the filter cake was supplied by Nova Gália, a sugar-alcohol company located in the city of Paraúna, Goiás State, Brazil. The cassava processing waste used was supplied by Cooperabs, a mixed cooperative of small producers of cassava starch and derivatives from the “CARA” region, located in the rural area of the city of Bela Vista, State of Goiás, Brazil (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Location of the municipalities that provided the agro-industrial waste

Source: Authors

Figure 1 shows the locations of the municipalities that provided the agro-industrial waste used to carry out the research. The inoculum selected for both wastes for the experiments was fresh cattle manure. This was collected (about 1.5 kg) from a cattle farm located in the municipality of Aparecida de Goiânia, State of Goiás, Brazil. To prepare the inoculum, it was diluted 1/1 with non-chlorinated water, sieved < 2mm, transferred to tubes and heated using the Bain Marie method (38°C).

The biomass (filter cake and cassava peel) was drained through the industrial process, crushed, sieved through a sieve with a mesh size of < 2 mm, and stored frozen (temperature ≈-80 C). Subsequently, the dry matter (MS) was determined after drying a sample in an oven at 1030C - 1050C, according to the methodology of APHA et al. (2012).

The amount of Total Solids (TS), Volatile Organic Solids (VOS or MSO) and inorganic dry mass Ash (Cz) was determined according to the procedure described in APHA et al. (2012). The values found in the biomass are shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Analysis of the dry mass TS (Total Solids), dry organic mass VOS

(Volatile Organic Solids) and Cz (inorganic dry mass) of the substrates

sugarcane bagasse and sugarcane filter cake

|

Agro-industry substrate |

TS (% m/m) |

VOS (% of TS) |

Cz (% of TS) |

|

Sugarcane bagasse |

85.810 |

86.074 |

3.936 |

|

Filter cake |

41.450 |

36.813 |

63.197 |

Source: Authors

2.2 Experimental methods

AD was carried out in 500 mL glass reactors on a discontinuous scale (experiments carried out at the Chemistry Laboratory of the Federal Institute of Goiás, located in the city of Goiânia, Capital of the State of Goiás, Brazil).

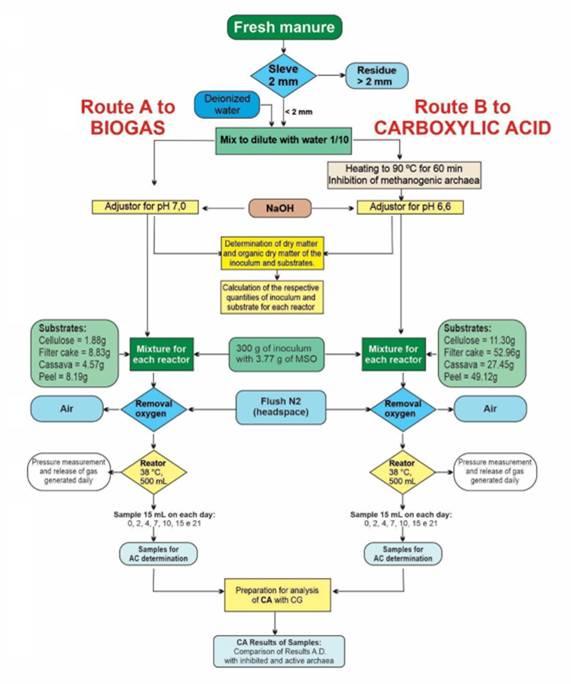

For the AD tests, a batch method adapted from Sträuber et al. (2018) was chosen. Two experimental series were carried out to compare the generation of biogas and AC in AD experiments. The first was carried out in the form of conventional tests with good conditions for all types of microorganisms in the process with pH = 7.0; and the second took place under contrasting conditions with pH < 6.6 for methanogenic microorganisms such as archaea.

The experimental mixtures in the reactors were: (i) pure inoculum; (ii) inoculum + microcrystalline cellulose; (iii) inoculum + filter cake; (iv) inoculum + cassava pulp; and (v) cassava pulp.

All the experiments were carried out in triplicate on both routes simultaneously. Figure 2 illustrates the flowchart of the experimental AD methods comparing the two routes, with the A Route focusing on biogas with active methanogens; and the B Route for the preferential production of CA and with inhibited methanogens.

2.2.1 CA production procedure

Based on the system of batch digestion experiments applied by the German partners of Harnisch et al. (2016), anaerobic reactors were prepared from glass jars with a volume of 500 mL, sealed with a glass cap for penicillin jars, thus allowing gases and liquids to be extracted later through a septum tube.

Figure 2: Flowchart of the experimental AD methods comparing Routes A and B

Source: Authors

The fresh inoculum, cow manure, was diluted with 1/1 non-chlorinated water, and underwent a process of inhibition of methanogenic archaea at a constant temperature of 90°C for a period of 60 minutes (Sträuber et al., 2018). Subsequently, by adding hydrochloric acid (HCA) of 1M concentration, pH = 6.6 was adjusted. Finally, the inoculum was stored for seven days using the Bain Marie technique at 38°C.

Following the procedures of Sträuber et al. (2018), seven samples were taken on days 0, 2, 4, 7, 10, 15 and 21 to achieve the generation of carboxylates. The samples were stored in a freezer (-8oC). The results of the AD experiment of 30 reactors: (i) 15 with active Archaea and (ii) 15 with injected Archaea were analyzed in the database using the Microsoft Office Excel spreadsheet, Windows Operating System, version 2010.

2.2.2 Determination of short chain fatty acids (SCFA)

To determine the short-chain fatty acids (SCFA) in the samples, a selectivity test was performed based on the laboratory validation of quantitative chromatographic methods, following the protocol described by Sousa and Silva et al. (2020). The method allowed for the quantitative analysis of acetic, propionic, butyric, isobutyric, valeric, and isovaleric acids.

The analytical curves were constructed using certified standards of each SCFA at different concentrations, ensuring a wide and representative analytical range. Linearity was evaluated by linear regression analysis (y = ax + b, where y is the peak area and x is the analyte concentration). The correlation coefficient (R² ≥ 0,995) was used to assess the goodness of fit. The selectivity of the method was confirmed by the resolution between peaks, and retention times were compared to those of standard solutions. The homogeneity of variance was tested using Cochran's Q test, supporting the assumption of a linear method.

Limits of detection (LOD) and quantification (LOQ) were calculated based on signal-to-noise ratios, establishing the method's sensitivity for the detection and quantification of SCFAs in the analyzed matrices.

Analyses were conducted at the Animal Nutrition Laboratory of the Department of Animal Science, Federal University of Goiás (DZO-UFG), Samambaia Campus, located in Goiânia, State of Goiás, Brazil.

SCFA concentrations were monitored across seven timepoints (days 0, 2, 4, 7, 10, 15, and 21) during two experimental cycles, involving five treatments conducted in triplicate: pure inoculum, inoculum plus microcrystalline cellulose, inoculum plus filter cake, and inoculum plus two types of cassava processing residues.

Chromatographic data were initially obtained as millimoles per liter (mMol/L) and later converted into milligrams of the respective carboxylic acid per gram of organic dry matter (ODM), also referred to as volatile solids (mg/gMSO), to standardize the results based on substrate content.

The sample preparation and extraction procedure followed the Analytical Run protocol for SCFA determination developed by the Laboratory of Bromatology and Animal Reproduction (ESALQ/USP), Department of Animal Science, located in Piracicaba, São Paulo, Brazil.

For the chromatographic procedure, 2.0 mL of the liquid fraction of each sample was centrifuged at 15,000 g for 15 minutes at 4°C. From the supernatant, 0.8 mL was transferred to a chromatographic vial, followed by the addition of 0.4 mL of a 3:1 acid solution consisting of 25% metaphosphoric acid and 98%–100% formic acid, and 0.2 mL of a 100 mM 2-ethylbutyric acid solution, used as an internal standard.

An aliquot of 1 µL of this extract was injected into a Shimadzu GC-2014 Gas Chromatograph (Series C119451-00513), equipped with a refractive index detector (RID-6A) and a Nukleogel ION 300 OA column with pre-column (Macherey-Nagel GmbH & Co. KG, Düren, Germany). The system allowed for precise separation and detection of the SCFAs.

Quantification was carried out by external calibration, comparing peak areas and retention times with those of the standard solutions. For statistical analysis, SCFA concentrations were also transformed into molar ratios (mM/100mM), representing the proportion of each acid relative to the total SCFA concentration in the sample.

2.2.3 Estimating the potential for conversion to SCFA in filter cake in the brazilian sugar-energy chain

Turkey's 5% test was applied to the values obtained for SCFA production (acetic acid, propionic acid, isobutyric acid, butyric acid, isovaleric acid and valeric acid). A simulation was also carried out of the production potential through the AD of the substrate in the Brazilian sugar-energy sector, taking into account data from UNICA (2022) which indicated production in the 2021/2022 harvest.

3 Results and Discussion

3.1 Results

3.1.1 SCFA's production potential

The test of the accumulated potential production of total and compartmentalized SCFA (acetic acid, propionic acid, isobutyric acid, butyric acid, isovaleric acid and valeric acid) at 21 days for the Routes, for the two agro-industrial residues and bovine manure inoculum, are shown in Table 2. The highest accumulations occur in Route B (with Archea inhibition) for sugarcane filter cake (2 734 mg/g of MSO) with a predominance of acetic acid (1 505 mg/g of MSO) and butyric acid (962 mg/g of MSO). It can be seen that in Route A (without Archea inhibition), the filter cake showed interesting CA values in the production of propionic acid (119 mg/g of MSO) with the waste from the sugar-energy sector. For cassava peel, due to the low overall performance (0.00 mg/g of MSO), the results for this substrate have not been discussed in detail.

Table 2: Total and accumulated SCFA contents at 21 days, obtained by two AD routes

in two agro-industrial residues (sugarcane filter cake and cassava peel)

through AD of the substrate with bovine manure inoculum

|

mg/g MSO of acid accumulated in 21 days |

||||||||

|

Route |

Acetic |

Propionic |

Isobutyric |

Butyric |

Isovaleric |

Valeric |

Total |

|

|

Filter cake from sugarcane |

||||||||

|

B |

1505a |

77b |

95a |

962a |

90a |

5b |

2734a |

|

|

A |

175b |

119a |

11b |

63b |

6b |

23a |

397b |

|

|

Cassava peel |

||||||||

|

B |

0c |

0c |

0c |

0c |

0c |

0c |

0c |

|

|

A |

2c |

1c |

0c |

2c |

1c |

1c |

6c |

|

Source: Authors

Table 2 shows that, for the filter cake residue, the averages with different letters (a, b) indicate a statistically significant difference. As for the cassava peel residue, there are two averages (A and B) with the same letter (c), indicating that there is no statistically significant difference between them, and they are considered equivalent.

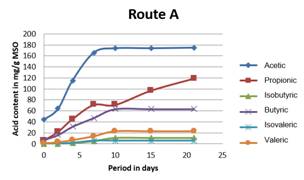

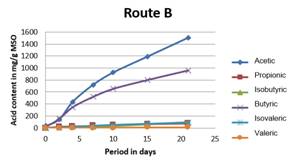

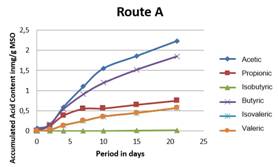

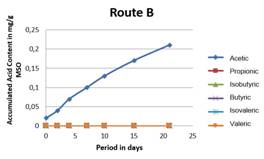

Figure 3 and Figure 4 show the accumulated production values at 21 days of total and compartmentalized SCFA (acetic acid, propionic acid, isobutyric acid, butyric acid, isovaleric acid and valeric acid) for Routes A and B respectively, for sugarcane filter cake and cassava peel. It can be seen that in Route B for filter cake there is a constant accumulation of acetic and butyric acids up to 21 days. Route B showed twice as many values at five days as Route A (Figure 2). Analyzing the graph in Figure 3 (Route A), it can be seen that maximum production occurred for all the acids between 5 and 10 days. An exception was propionic acid (mg/g MSO), with a second production peak after 10 days.

Figure 3: Accumulated production of total and compartmentalized SCFA (acetic acid,

propionic acid, isobutyric acid, butyric acid, isovaleric acid and valeric acid

(mg/g MSO)) for routes A and B through AD of the filter cake substrate

Source: Authors

Figure 4 shows that the accumulated production of SCFA at 21 days was less than 3 mg/g of MSO, indicating the low potential of cassava peel in the experimental procedures adopted.

Figure 4: Cumulative production of total and compartmentalized SCFA (acetic acid, propionic acid, isobutyric acid, butyric acid, isovaleric acid and valeric acid) for A and B Routes through AD of cassava peel substrate

Source: Authors.

Still referring to Figure 4, it can be seen that the accumulated concentration at 21 days presented significant values in the filter cake samples from Route B (where methanogenic microorganisms are inhibited), obtaining 2 734 mg/g of MSO of total SCFA. Route A presented higher levels of acetic acid (175 mg/g of MSO) and propionic acid (119 mg/g of MSO) with production peaks between 5 and 10 days. In both cassava peel routes, SCFA production did not show significant results (low values), and there is no justification for using these technologies on this agro-industrial waste.

The most significant values of propionic acid in Route A for the filter cake may indicate a potential when this acid is of interest for production, mainly in reactors with low hydraulic retention time.

The graphs in Figure 5 show the relative proportion of SCFA in percentage of acetic acid, propionic acid, isobutyric acid, butyric acid, isovaleric acid and valeric acid, with the respective concentrations in percentages (%) for Route B that could be used in the sugarcane industry for the production of acetic acid and butyric acid.

Figure 5: Relative production of SCFA as a percentage (%) of acetic acid, propionic acid, isobutyric acid, butyric acid, isovaleric acid and valeric acid for B Route, through the AD of the filter cake substrate

Source: Authors.

3.1.2 Estimating the potential for conversion to SCFA in filter cake in the brazilian sugar-energy chain

The values shown in Table 3 were used to simulate the potential production of SCFA as a percentage of acetic acid, propionic acid, isobutyric acid, butyric acid, isovaleric acid and valeric acid, using the filter cake substrate in Route B, considering the production of residues in the 2021/2022 sugarcane harvest in Brazil indicated by UNICA (2022), which indicated production in the 2021/2022 harvest until January 1, crushing reached around 613.6 million tons (UNICA, 2022). The processing of each ton of sugarcane results in around 40 kg of filter cake as waste, of which: 613.6 million tons of sugarcane; 24.5 million tons of filter cake/year in Brazil; and 2.5 million tons of filter cake/year in the State of Goiás, Brazil.

Table 3: Estimating the potential for conversion to SCFA in filter cake in the Brazilian sugar-energy chain as a percentage of in percentage of acetic acid, propionic acid, isobutyric acid, butyric acid, isovaleric acid and valeric acid for B Route through the AD of the filter cake substrate

|

Acid |

Percentage(%) |

Production (t/year) |

|

Acetic |

43 |

3,830,000 |

|

Propionic |

7 |

534,000 |

|

Isobutyric |

3 |

267,000 |

|

Butyric |

40 |

3,562,000 |

|

Isovaleric |

4 |

356,000 |

|

Valeric |

4 |

356,000 |

Source: The authors

Considering the data obtained in this work and those indicated by Leite et al. (2015) and Bernardino et al. (2018), an estimate was obtained of the potential for conversion to SCFA in filter cake in the Brazilian sugar-energy chain relative to SCFA as a percentage of acetic, propionic, isobutyric, butyric, isovaleric and valeric acids for routes B by means of the AD of the filter cake substrate (Table 3).

3.2 Discussion

Organic waste AD technology, which is known as “clean technology”, contributes directly to sustainable development, improving energy yields without harming the environment, and even contributing to its improvement.

Brazil is currently an international leader in the production of energy from biomass, as 27.4% of its energy matrix comes from the use of these renewable resources, 19% of which are products originating from sugar cane, which no country in the world has in its matrix in such a high quantity.

The bioproduction of AC via AD technology with organic waste from agro-industrial activities contributes to reducing environmental impacts by reducing the waste generated. In Brazil, the organic waste and wet residues available for the generation of platform chemicals, especially with methanogenic inhibition for CA production, could be an environmentally sustainable way to meet the challenges associated with the growing demand for energy and help build the bioeconomy of the future.

Our applied biotechnological methods contribute to improving sustainability by generating carboxylate acids from agro-industrial waste available in Brazil's sugar-energy sector. The production of CA showed better results from organic waste from sugarcane filter cake in Route B. With the inhibition of methanogenic archaea, according to Grootscholten et al. (2013), hydrolysis is the slowest stage of AD and is considered limiting in the degradation of organic waste, in which complex polymers (lipids, proteins and carbohydrates) are transformed into smaller soluble organic compounds (fatty acids, amino acids and glucose).

Strategies are therefore adopted to speed up the hydrolysis process by optimizing operational factors and applying pre-treatment to organic waste before AD, in order to improve the hydrolysis rate and increase the availability of organic matter in the soluble fraction. In the acidogenic stage, AD occurs from metabolic pathways that coexist in anaerobic processes, which determine products formed by directing pyruvic acid, which can be bio-converted into various products (acetate, propionate, butyrate, ethanol, propanol, butanol, hydrogen and carbon dioxide).

The direction of the metabolic pathway, which is related to the operating parameters adopted in the acidic stage. Thus, the parameters used experimentally in Route B were appropriate, such as the type of inoculum, substrate, pH, temperature and hydraulic retention time used by the sugar-energy industry after scaling-up research according to the recommendations of Sousa e Silva et al. (2020) and De Groof et al. (2019).

According to Zhou et al. (2018), inoculums of anaerobic origin with inhibition of methanogenic microorganisms, with a pH close to 7.0 and a temperature above 30°C are factors that generally accelerate the kinetics of the acidogenesis reaction, resulting in faster production of acetate, an acid that is formed in greater quantities during the AD process (Zhou et al., 2018).

Brazil is the largest producer of sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum species). It is a world exporter of sugar, which is also used to produce ethanol as a vehicle fuel (Frick, 2018).

Filter cake is a residue from the pre-treatment of sugar cane. It is a mixture of wet sugarcane bagasse and settling sludge from the sugar clarification process (Bernardino et al., 2018).

Cassava peel as a substrate was not a suitable raw material for the production of CA in both routes. It is necessary to carry out laboratory research using other types of inoculum. As reported by Khanal (2008), acetogenesis involves the oxidation of alcohols and organic acids to produce hydrogen and acetate. This stage is carried out by acetogenic bacteria, converting volatile fatty acids and ethanol into acetic acid, hydrogen and carbon dioxide. The low concentration of volatile organic mass in the cassava peel provided the least significant results in this study for both Routes.

According to Pham Van et al. (2018) there are strategies to increase the availability of organic matter in the soluble fraction and facilitate its subsequent bioconversion to CA, when the hydrolysis rate is improved. Future research is therefore recommended using the methods adopted, but employing chemical (acid and alkaline), physical (thermal, microwave and ultrasound) and biological (enzymes) pre-treatments, as recommended by Fdez-Güelfo et al. (2011) to improve the performance of CA production for cassava peel waste.

Therefore, with regard to the waste used (sugar cane filter cake and cassava peel processing, with cattle manure as inoculum), no references have been found in the literature to date. Thus, the results obtained with these organic agro-industrial residues from Brazil for the production of carboxylic acids (CA) by anaerobic digestion (AD) with inhibited archaea is an unprecedented contribution.

The production of CA on a laboratory scale, using sugarcane filter cake as a substrate and fresh bovine manure as an inoculum, showed very significant values of acetic and butyric acids.

The production of energy through biogas from sugar cane can take advantage of the existing production of propionic acid.

The expansion of the use of biomass energy must be well planned and managed in the interests of sustainability and environmental preservation, including soil quality, air quality, water resources and biomes, without competing with food production.

4 Conclusion

Organic waste AD technology can contribute to reducing environmental impacts by reducing agro-industrial waste generated when applied to energy production.

The biotechnological methods applied in the research contribute to improving sustainability for generating CA using the AD process with interrupted methanogenesis, from agro-industrial waste available in the State of Goiás, Brazil.

The results showed that CA production on a laboratory scale showed relatively low values with cassava peel processing waste as a substrate, indicating the need to carry out laboratory research using other types of inoculum and/or other types of methodology/technology. On the other hand, CA production on a laboratory scale was significant for sugarcane filter cake waste as a substrate and fresh bovine manure as an inoculum.

This study provides insights into the development of interrupted methanogenesis AD technology for the production of SCFA from agro-industrial organic waste.

The SCFA identified in the samples were acetic acid, propionic acid, isobutyric acid, butyric acid, isovaleric acid and valeric acid. They are potential renewable carbon sources that can be used to produce fuels or chemicals.

The production of energy from sugar cane has assumed an important role of stability in the system of electricity generation, via AD technology in Brazil, due to the volume of production that increases significantly between the months of April and October. These months correspond to the driest period of the year, when water reservoirs struggle to meet all the demand for electricity.

5 Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Chemistry Laboratory of the Federal Institute of Goiás (IFG), Goiânia Campus, in the city Goiânia, State of Goiás, Brazil; the sugar and alcohol company, Nova Gália, located in the city of Paraúna, State of Goiás, Brazil; Cooperabs, a mixed cooperative of small producers of cassava starch and derivatives in the “CARA” region, located in the city of Bela Vista, State of Goiás, Brazil; the Animal Nutrition Laboratory of the Zootechnics Department of the Federal University of Goiás (UFG), Samambaia Campus, in the city Goiânia, State of Goiás, Brazil; and the carboxAiD* Project, Helmholtz-Zentrum für Umweltforschung GmbH - UFZ in the city of Leipzig, State of Saxony, Germany. A special acknowledgment is dedicated to Prof. Dr. Joachim Werner Zang (in memoriam), who served as the coordinator in Brazil. He was also a valued researcher in the Professional Master's Degree Program in Technology, Management, and Sustainability (PPGTGS) at IFG, Campus Goiânia, in the city of Goiânia, State of Goiás, Brazil.

*https://www.ufz.de/carboxaid/index.php?en=46924.

Bibliographical references

ABBASI, T.; TAUSEEF, S. M.; ABBASI, S. A. Anaerobic digestion for global warming control and energy generation — An overview. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 16(5), 3228-3242, 2012. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2012.02.046

AGLER, M.T.; WRENN, B.A.; ZINDER, S.H.; ANGENENT, L.T. Waste to bioproduct conversion with undefined mixed cultures: the carboxylate platform. Trends in biotechnology, 29 2, 70–8, 2011. DOI:10.1016/j.tibtech.2010.11.006

ALMEIDA, M. A. A. L. D. S. Análise semiquantitativa de microplásticos na água de torneira na cidade de Brasília-Distrito Federal. (Tese de doutorado) Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciências da Saúde, Universidade de Brasília, DF, Brazil, 2021.

ALREFAI, A.M.; ALREFAI, R.; BENYOUNIS, K.Y.; STOKES, J. Impact of Starch from Cassava Peel on Biogas produced through the anaerobic digestion process. Energies, 13(11), 2713, 2020. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/en13112713

APHA (American Public Health Association); AWWA (American Water Works Association) and WEF (Water Environment Federation). Standard methods for the examination of water and wastewater. 22th Edition. Washington, DC, Press, 2012. Available at: <http://www.standardmethods.org>. DOI: 10.2105/SMWW.2882.030. Accessed on 2025, May 20.

ARAÚJO, A. V.; FEROLDI, M.; URIO, M. B. Uso De Biogás Em Máquinas Térmicas. Journal of Agronomic Sciences, Umuarama, v. 3, n. Especial, p.274-290. ISSN Print: 2156-8553, 2014. ISSN Online: 2156-8561.

ATELGE, M. R.; ATABANI, A. E.; BANU, J. R.; KRISA, D.; KAYA, M.; ESKICIOGLU, C.; KUMAR, G.; LEE, C.; YILDIZ; UNALAN, S.; MAHANASUNDARAM, R.; DUMAN, F. A critical review of pretreatment technologies to enhance anaerobic digestion and energy recovery. Fuel, 270: 117494, 2020. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2020.117494.

BERNARDINO, C. A. R.; MAHLER, C. F.; VELOSO, M. C. C.; ROMEIRO, G. ASCHROEDER, P. Torta de Filtro, Resíduo da Indústria Sucroalcooleira - Uma Avaliação por Pirólise Lenta Filter Cake, Residue of the Sugarcane Industry - A Evaluation by Slow Pyrolysis. In Rev. Virtual Química, 10, p. 551–573, 2018. DOI:10.21577/1984-6835.20180042.

BHATT, A. H.; REN, Z.J.; TAO, L. Value proposition of untapped wet wastes: carboxylic acid production through anaerobic digestion. Iscience, v. 23, n. 6, 2020. DOI:10.1016/j.isci.2020.101221

CAGNETTA, C.; COMA, M.; VLAEMINCK, S. E.; RABAEY, K. Production of carboxylates from high rate activated sludge through fermentation. Bioresource technology, 217, 2016: p. 165-172. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2016.03.053

CHEN, Y.; CHENG, J. J.; CREAMER, K. S. Inhibition of anaerobic digestion process: a review. Bioresource technology, 99.10: p. 4044-4064, 2008. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2007.01.057

CIBIOGÁS (CENTRO INTERNACIONAL DE ENERGIAS RENOVÁVEIS - Biogás). Panorama do biogás no Brasil, 2022. Available at:https://cibiogas.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/NT-PANORAMA-DO-BIOGAS-NO-BRASIL-2021.pdf. Accessed at: 06/03/2023.

CUI, H. W. ; CHEN, Y. T.; CHEN, Y. W.; DOLFING, J.; LI, B. Y.; SUN, Z. Y.; TANG, Y. Q.; HUANG, Y. L.; DAI, W. Y.; CUI, Q. J.; CHEN, X.; JIAO, S. B. Metagenomic insights into microbial mechanisms of pH shifts enhancing short-chain carboxylic acid production from fruit waste anaerobic fermentation. Industrial Crops and Products, 2024, 222: 119520. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2024.119520

DE CLERCQ, D.; WEN, Z.; GOTTFRIED, O., SCHMIDT, F.; FEI, F. A review of global strategies promoting the conversion of food waste to bioenergy via anaerobic digestion. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 79, 204-221, 2017. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2017.05.047

DE GROOF, V.; COMA, M.; ARNOT, T.; LEAK, D.J.; LANHAM, A.B. Medium Chain Carboxylic Acids from Complex Organic Feedstocks by Mixed Culture Fermentation. Molecules, v. 24, n. 3, p. 398, 2019. DOI:https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules24030398.

DOMINGOS, J. M.; MARTINEZ, G. A.; SCOMA, A.; FRARACCIO, S.; KERCKHOF, F. M.; BOON, N.; REIS, M. A. M.; FAVA, F.; BERTIN, L. Effect of operational parameters in the continuous anaerobic fermentation of cheese whey on titers, yields, productivities, and microbial community structures. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering, v. 5, n. 2, p. 1400-1407, 2017. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1021/acssuschemeng.6b01901

FDEZ-GUELFO, L.A.; GALLEGO, C. A.; SALES, D.; ROMERO, L.I. The use of thermochemical and biological pretreatments to enhance organic matter hydrolysis and solubilization from organic fraction of municipal solid waste (OFMSW). Chemical Engineering Journal, 168, p. 249–254, 2011. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2010.12.074.

FORMANN, S.; HAHN, A.; JANKE, L.; STINNER, W.; STRAUBER, H.; LOGROÑO, W.; NIKOLAUSZ, M. (2020) Beyond Sugar and Ethanol Production. Value, Generation Opportunities Through Sugarcane Residues. Frontiers in Energy Research, p. 1–21. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3389/fenrg.2020.579577

FRICK, F. Efeito da adição fracionada de bolo de filtro na digestão anaeróbica da vinhaça (Dissertação de mestrado). Universidade Federal do Paraná, Palotina, PR, Brazil, 2018.

GOIS, I. M.; BOWERS, C. M.; KIM, B. C.; FLICK, R.; LAWSON, C. E. . Distinct Acetate Utilization Strategies Differentiate Butyrate and Octanoate Producing Chain-Elongating Bacteria. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. bioRxiv, 2025,05. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1101/2025.05.02.651941

GROOTSCHOLTEN, T.I.M.; STEINBUSCH, K.J.J.; HAMELERS, H.V.M.; BUISMAN, C.J.N. High rate heptanoate production from propionate and ethanol using chain elongation. Bioresource Technology, v. 136, p. 715-718, 2013. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech. 2013.02.085.

GUSTAFSSON, M.; MENEGHETTI, R.; SOUZA MARQUES, F.; TRIM, H.; DONG, R.; AL SAEDI, T.; RASI, S.; THUAL, J.; KORNATZ, P.; WALL, D.; BERNTSEN, C.; SAXEGAARD, S.; LYNG, K.A.; NÄGELE, H.J.; HEAVEN, S.; BYWATER, A. A perspective on the state of the biogas industry from selected member countries. Gustafsson, M., Liebetrau, J. (Ed.) IEA Bioenergy Task 37, 2024:2, ISBN 979-12-80907-43-1,2024.

HARNISCH, F.; ROSA, L.; MORGADO, F.; STRAUBER, H.; KLEINSTEUBER, S.; ZECHENDORF, M.; R., D.S.T.; SCHRODER, U. DE102014214582A120160128 - Verfahren zur Herstellung von organischen Verbindungen (Patent).

JEYAKUMAR, R. B.; VINCENT, G. S. Recent advances and perspectives of nanotechnology in anaerobic digestion: A new paradigm towards sludge biodegradability. Sustainability, v. 14, n. 12, p. 7191, 2022. DOI:https://doi.org/10.3390/su14127191

KHANAL, S.K. Anaerobic Biotechnology for Bioenergy Production: Principles and Applications. Wiley-Online Library. Print ISBN:9780813823461, 2008.

KHIEWWIJIT, R.; TEMMINK, H.; LABANDA, A.; RIJNAARTS, H.; KEESMAN, K. J. Production of volatile fatty acids from sewage organic matter by combined bioflocculation and alkaline fermentation. Bioresource technology, 197: p. 295-301, 2015. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2015.08.112

LEE, W. S.; CHUA, A. S. M.; YEOH, H. K.; NGOH, G. C. A review of the production and applications of waste-derived volatile fatty acids. Chemical Engineering Journal, v. 235, p. 83-99, 2014. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2013.09.002

LEITE, A.F.; JANKE, L.; HARMS, H.; ZANG, J.W.; FONSECA-ZANG, W.A.; STINNER, W.; NIKOLAUSZ, M. Assessment of the Variations in Characteristics and Methane Potential of Major Waste Products from the Brazilian Bioethanol Industry along an Operating Season. Energy and Fuels, 7, p. 4022–4029, 2015. DOI:doi.org/10.1021/ef502807s

LU, X.; QIU, S.; LI, Z. and GE, S.. Pathways, challenges, and strategies for enhancing anaerobic production of short-chain and medium-chain carboxylic acids from algal slurry derived from wastewater. Bioresource Technology, 131528, 2024. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2024.131528

MATA-ALVAREZ , J.; DOSTA, J.; ROMERO-GÜIZA, M.S. ; FONOLL , X.; PECES, M.; ASTALS, S. A critical review on anaerobic co-digestion achievements between 2010 and 2013. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 36, p. 412-427, 2014. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2014.04.039.

OGWU, M. C.; IYIOLA, A. O.; FAWOLE, W. O. ; IZAH, S. C; VAZQUEZ-ARENAS, J.G.; FELEKE, S.T.; WEI, X. Biobased Resource Recovery Techniques in the Global South. In - Sustainable Bioeconomy Development in the Global South. Springer, Singapore, 2025. ISBN: 978-981-96-0304-6. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-96-0305-3_17

PHAM VAN, D.; HOANG, M.G.; PHU..; P., S.T.; FUJIWARA, T. Kinetics of carbon dioxide, methane and hydrolysis in co-digestion of food and vegetable wastes. Global Journal of Environmental Science and Management, v. 4, n. 4, p. 401-412, 2018. DOI:10.22034/gjesm.2018.04.002.

RAMIO-PUJOL, S.; GANIGUE, R.; BANERAS, L.; COLPRIM, J. How can alcohol production be improved in carboxydotrophic clostridia? Process Biochemistry, 50(7), 1047–1055, 2015. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procbio.2015.03.019.

REDDY, M.V.; MOHAN, S.V.; CHANG, Y.C. Medium-chain fatty acids (MCFA) production through anaerobic fermentation using Clostridium kluyveri: effect of ethanol and acetate. Applied biochemistry and biotechnology, 185, p. 594–605, 2018. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12010-017-2674-2

REDDY, M.V.; NANDAN REDDY, V.U.; CHANG, Y.C. Integration of anaerobic digestion and chain elongation technologies for biogas and carboxylic acids production from cheese whey. Journal of Cleaner Production, 132670, 2022. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.132670.

REN, W.; ZHANG, Y.; LIU, X.,; LI, S.,; LI, H. and ZHAI, Y. . Peracetic acid pretreatment improves biogas production from anaerobic digestion of sewage sludge by promoting organic matter release, conversion and affecting microbial community. Journal of Environmental Management, 349, 119427, 2024. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2023.119427

ROMANO, R.T.; ZHANG, R. Co-digestion of onion juice and wastewater sludge using an anaerobic mixed biofilm reactor. Bioresource Technology, v. 99, n. 3, p. 631-637, 2008. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2006.12.043

SAADOUN, L.; CAMPITELLI, A.; KANNENGIESSER, J.; STANOJKOVSKI, D.; MANDI, L.; OUAZZANI, N. Co‐digestion of olive mill wastewater and municipal solid waste landfill leachate promotes medium‐chain fatty acids and hydrogen production. Biofuels, Bioproducts and Biorefining, 2025,https://scijournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/bbb.2731. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/bbb.2731

SHAH, M. P.; SHAH, N. (Eds.). (2024). Environmental Approach to Remediate Refractory Pollutants from Industrial Wastewater Treatment Plant. ISBN: 978-0-443-13884-3. Elsevier. Website: https://www.elsevier.com/books-and-journals

SHEN, D.; YIN, J.; YU, X.; WANG, M.; LONG, Y.; SHENTU, J.; CHEN, T. Acidogenic fermentation characteristics of different types of protein-rich substrates in food waste to produce volatile fatty acids. Bioresource Technology, 227: p. 125-132, 2017. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2016.12.048

SHESKIN, D. J. Handbook of parametric and nonparametric statistical procedures. Chapman and Hall/CRC, 3rd Edition, New York, 2003.

SOUSA E SILVA, A.; MORAIS, N.W. S.; COELHO, M. M. H.; PEREIRA, E. L.; SANTOS, A. B. Potentialities of biotechnological recovery of methane, hydrogen and carboxylic acids from agro-industrial wastewaters. Bioresource Technology Reports, 10, 100406, 2020. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biteb.2020.100406.

STEINBUSCH, K. J. J.; HAMELERS, H.V.M.; PLUGGE, C.M.; BUISMAN, C.J.N. Biological formation of caproate and caprylate from acetate: fuel and chemical production from low grade biomass. Energy. Env. Sci. 4, p. 216–224, 2011. DOI: 10.1039/c0ee00282h

STRAUBER, H.; BUHLIGEN, F.; KLEINSTEUBER, S.; DITTRICH-ZECHENDORF, M. Carboxylic acid production from ensiled crops in anaerobic solid-state fermentation – trace elements as pH controlling agents support microbial chain elongation with lactic acid. Engineering in Life Sciences, 18, p. 447–458, 2018. DOI:10.1002/elsc.201700186.

UNICA - UNIÃO DA INDÚSTRIA DE CANA-DE-AÇÚCAR E BIOENERGIA. Moagem de cana registra crescimento de 3% na safra 22/23, 2022. Available at:https://unica.com.br/noticias/moagem-de-cana-registra-crescimento-de-3-na-safra/. Accessed at: 03/17/2023.

VICENTE, M.; GONZALEZ-FERNÁNDEZ, C.; NICAUD, J. M. and TOMÁS-PEJÓ, E. Turning residues into valuable compounds: organic waste conversion into odd-chain fatty acids via the carboxylate platform by recombinant oleaginous yeast. Microbial Cell Factories, 2025, 24(1), 32. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12934-025-02647-7

VELVIZHI, G.; JENNITA, J. P.; NAGARAJ P. S.; LATHA, K.; MOHANAKRISHNA, G.; AMINABHAVI , T. M.. Emerging trends and advances in valorization of lignocellulosic biomass to biofuels. Journal of Environmental Management , 345 , 118527, ISSN 0301-4797, 2023. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2023.118527

WANG, Y.; WU, S. L.; WEI, W.; WU, L.; HUANG, S.; DAI, X. AND NI, B. J.. pH-dependent medium-chain fatty acid synthesis in waste activated sludge fermentation: Metabolic pathway regulation. Journal of Environmental Management, 2025, 373, 123722. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2024.123722

ZHANG, B.; ZHANG, L. L.; ZHANG, S. C.; SHI, H. Z.; CAI, W. M. The influence of pH on hydrolysis and acidogenesis of kitchen wastes in two-phase anaerobic digestion. Environmental technology, v. 26, n. 3, p. 329-340, 2005. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1080/09593332608618563

ZHOU, M.; YAN, B.; WONG, J.W.C.; ZHANG, Y. Enhanced volatile fatty acids production from anaerobic fermentation of food waste: A mini-review focusing on acidogenic metabolic pathways. Bioresource Technology, v. 248, parte A, p. 68-78, 2018. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2017.06.121