The Relationship between Economic Growth and the Generation of Urban Solid Waste

Emile Lebrego Cardoso[1]

Vanusa Carla Pereira Santos[2]

Raul Ivan Raiol de Campos[3]

JéssicaAlmeida da Cunha[4]

Abstract

This study examined the relationship between economic growth and solid waste generation, aiming to analyze the correlation between economic growth represented by Brazil's Gross Domestic Product (GDP) from 2012 to 2019 and the generation of Urban Solid Waste during the same period. This analysis was based on the theory of Ecological Economics, specifically the second law of thermodynamics, the law of entropy, which states that the economic system extracts resources and low-entropy matter from the environment and returns high-entropy energy and matter, representing environmental degradation and disorder. The main objective of this study was to verify through descriptive statistics if there is a direct correlation between economic growth (GDP) and the generation of Urban Solid Waste (USW) measured in thousand tons per day, representing high entropy. There is a direct relationship between GDP growth and the generation of USW, which raises the research question: how is it possible to control and manage the generation of USW in the face of GDP growth? The methodology involved bibliographic, qualitative, and quantitative research, utilizing statistical data such as Pearson's correlation coefficient. The results indicate a significant correlation between GDP growth and USW generation, demonstrating a consistent increase in USW when there is a peak in GDP growth. This suggests that society tends to consume more disposable products in daily life, contributing to waste generation. The conclusion drawn was that GDP growth has become unsustainable as it fails to preserve natural resources and mitigate waste disposal and environmental damage caused by economic activities.

Keywords:Ecological Economics. Economic Growth. Law of Entropy. Solid Waste.

A Relação entre o Crescimento Econômico e a Geração de Resíduos Sólidos Urbanos

Resumo

Este estudo contextualizou a relação entre crescimento econômico e geração de resíduos sólidos, com o objetivo de analisar a correlação entre o crescimento econômico representado pelo Produto Interno Bruto (PIB) do Brasil de 2012 a 2019 e a geração de Resíduos Sólidos Urbanos no mesmo período. Essa análise foi baseada na teoria da Economia Ecológica, especificamente na segunda lei da termodinâmica, a lei da entropia, que afirma que o sistema econômico extrai recursos e matéria de baixa entropia do meio ambiente e retorna energia e matéria de alta entropia, representando degradação e desordem ambiental. O objetivo principal deste estudo foi verificar por meio de estatística descritiva se existe correlação direta entre o crescimento econômico (PIB) e a geração de Resíduos Sólidos Urbanos (RSU) medida em mil toneladas por dia, representando alta entropia. Verifica-se uma relação direta entre o crescimento do PIB e a geração de RSU, o que levanta a questão de pesquisa: como é possível controlar e gerenciar a geração de RSU diante do crescimento do PIB? A metodologia envolveu pesquisa bibliográfica, qualitativa e quantitativa, utilizando dados estatísticos como o coeficiente de correlação de Pearson. Os resultados indicam uma correlação significativa entre o crescimento do PIB e a geração de RSU, demonstrando um aumento consistente dos RSU quando há um pico de crescimento do PIB. Isso sugere que a sociedade tende a consumir mais produtos descartáveis no dia a dia, contribuindo para a geração de resíduos. A conclusãofoi que o crescimento do PIB se tornou insustentável, pois não consegue preservar os recursos naturais e mitigar o descarte de resíduos e os danos ambientais causados pelas atividades econômicas.

Palavras-chave: Economia Ecológica; Crescimento Econômico; Lei da Entropia; Resíduos Sólidos.

Recebido em: 16/09/2024

Aceito em: 14/01/2025

Publicado em: 15/05/2025

1 Introduction

Since the mid-eighteenth century, the way of producing and consuming goods and services has been innovative. Factors such as technology, electricity, and fuel, have enabled the production of goods on a larger scale, encouraging increased consumption and waste, which inevitably affects the quality of the environment and consequently the well-being of humanity (Zarinato; Rotondaro, 2016). However, until the beginning of the twentieth century, raw resources were considered infinite, inexhaustible, and extracted without any precaution regarding their prolonged use. This perception of nature as a “free good" in neoclassical economics has led to increasingly aggressive exploitation practices aimed at maximizing capital profitability without considering the environmental damage caused (Cavalcanti, 2015).

Cavalcanti (2017) argues that conventional (linear) economics views the economic system as separate from the environment, treating the latter as an external factor to the production process, and thus ignoring its role in maintaining balance of the environment. Consequently, the linear economy undervalues the services and goods produced, especially the inputs from nature, which are essential raw materials in the production process. By neglecting how energy and matter are used and disposed of back into the environment, the concerns highlighted in the second law of thermodynamics, the law of entropy are evident. This law shows that the economic system extracts resources and matter of low entropy from the environment and returns energy and matter of high entropy, representing environmental degradation and disorder (Melgar-Melgar; Hall, 2020).This is in accordance with the hypothesis presented in this article.

Rudolf Clausius was the first to coin the term entropy in 1868.The entropy law asserts that energy transformed from one state to another refers to states of available energy versus unavailable energy. The unavailable energy is pollution. "In fact, pollution is the sum total of all the available energy in the world that has been transformed into unavailable energy. Waste, then, dissipated energy" (Rifkin; Howard, 1980, p.35). The authors also assert that energy moves from a state of order, with lower entropy and higher energy concentration, to a state of disorder, with higher entropy and dissipated energy.

Authors of Ecological Economics (EE) such as Georgescu-Roegen (1989) and Daily (1996), developed the idea that economics has a direct relationship with the laws of thermodynamics, especially regarding the law of entropy. This law addresses the quality of power laid out in a system. According to this theory, the economy is a subsystem within a larger system, the environment, and is not a closed and isolated system, as it withdraws resources from and returns waste to larger open system (Cavalcanti, 2017).

For EE, the entropic process serves as a warning for the depletion of natural capital, and it is important to control the transformation of energy quality by reducing consumption and changing production patterns (Oliveira, 2017). In the environment, low-entropy energy is available, represented by the raw resources used in the economic process to manufacture goods and services. This low-entropy energy represents high-quality (useful) energy, that once used, becomes low-quality (useless) energy in the form of environmental deterioration, loss of biodiversity, pollution, and solid waste generation. This high entropy does not disappear, as per the first law of thermodynamics stating that "energy cannot be destroyed or created", so all the high entropy created will persist somewhere (Glaucina; Mayumi, 2010; Winckler; Renk, 2017).

Given the above, the main objective of this study is to verify through descriptive statistics if there is a direct correlation between economic growth (GDP) and the generation of Urban Solid Waste (USW) measured in thousand tons per day, representing high entropy. There is a direct relationship between GDP growth and the generation of solid waste, which raises the research question: how is it possible to control and manage the generation of solid waste in the face of GDP growth?Therefore, the following hypotheses were considered: (H0) There is a correlation between the growth of the economy expressed by the evolution of the Brazilian GDP and the generation of USW; (H1) there is no direct correlation between the growth of the economy expressed by the evolution of the Brazilian GDP and the generation of USW.This article is structured as follows: introduction presented here; theoretical framework, methodology; results and discussions, and final considerations.

2 Theoretical Framework

This section of the article explores the connection between the economy and the environment through the perspectives of Environmental Economics and Ecological Economics. Ecological Economics is particularly noted for its critique of economic growth, highlighting its limitations and disregard for environmental concerns. The concepts of Entropy and the Second Law of Thermodynamics are also emphasized as crucial for understanding environmental issues within the economic framework, providing a solid theoretical basis for further exploration.

2.1 Ecological Economics and Unsustainable Economic Growth

Classical authors like Adam Smith and Ricardo primarily focused on understanding the capitalist system and methods of production and capital accumulation, rather than environmental issues. However, Malthus, known for his theory of population growth, emphasized the limits of production due to constraints in nature. Malthus' ideas foreshadowed modern concerns about sustainability, natural resources, and environmental capacity (Malthus, 1992).

Stuart Mill was also concerned with environmental issues, as he believed that to achieve economic development, it would be necessary to consider qualitative issues, in addition to the analysis of GDP, which is a quantitative analysis. This author was influenced by various socialist authors who were concerned with social justice, quality of life, and social well-being (Mill. 1885).

Neoclassical authors did not directly discuss sustainability, as the focus of their discussions was on the efficient allocation of resources and market equilibrium. However, Pareto, when discussing the concept of efficiency (Pareto optimality), developed elements that can be applied or used in environmental analyses. In other words, even without discussing sustainability, Pareto developed discussions on the rational use of natural resources. (Pareto, 2014).

However, the first attempt to jointly address economics and the environment was with the discussions of Environmental Economics. However, for authors such as Menuzzi and Silva (2015), this theory presented flaws because it is based on neoclassical economics with its wealth-maximizing precepts, thus not presenting a view concerned with the maintenance of natural resources in the long term. According to this theory based on the production function (Y), the capital produced by humankind (K), labor (L), and natural capital (R), are perfectly interchangeable with each other. In this way, the expansion of the economy can occur without limits on the availability of natural resources, as these can be surpassed and replaced by other forms of capital due to technological advancement.

Y= (K) + (L) + (R)

where:

Y = production function

K = the capital produced by humankind

L = labor

R = natural capital

This concept of perfect replacement is also known as "weak sustainability". According to Cavalcanti (2004), all human activity inexorably interferes with the ecosystem, either through the extraction of natural resources or the disposal of waste in the form of degraded energy. Thus, for the author, nature is at the same time a source of life and a deposit of solid waste. Therefore, the concept of "weak sustainability" does not hold. To this end, in the mid-1970s, the concept of Ecological Economics (EE) emerged, proposing a new way of seeing and conceiving the economy, interconnecting economic interests with biological, chemical, and ecological factors.

One of the pioneers of EE was the Romanian researcher Georgescu-Roegen, who in 1971 approached EE from the second law of thermodynamics, calling the process "The law of entropy and the economic process". For Montibeller, Souza and Bôlla (2012) and Oliveira(2017), EE analyzes the economic system as an open subsystem, present in a larger system that is the ecosystem. Therefore, for its full functioning, the economic system depends on the capture of matter and energy from the environment, since the Earth is a thermodynamically closed system, the economy can not act in isolation from its biophysical basis that sustains its functioning (Lizarazo, 2018; Barbosa, Marques, 2015).

That said, EE proposes the idea of "strong sustainability" considering that natural capital (R) can not be perfectly replaced by other forms of capital, even if there is technological advancement (Menuzzi; Silva, 2015). From this current, the analysis made by the sustainable use of natural resources extracted from the environment and the concept of entropy is approached, given by the second law of thermodynamics to exemplify the circulation of energy and matter present in the production process, and its consequences (Cavalcanti, 2017). There are different strands to analyze EE. This study proposes using the theory critically, emphasizing the unsustainability of the orthodox economic system.

Therefore, EE criticizes economic growth because it is unlimited, without concern for the environment, sustained by the free market has found its limits imposed by nature itself (Lizarazo, 2018). The new alternative analysis questions that the economy is not a closed system with a flow between production and consumption, as neoclassical thinkers argue.

This unsustainability linked to economic growth is related to continuous environmental degradation, which imposes a regenerative overload on ecosystems, compromising not only environmental quality but also the maintenance of the human species itself (Coletti; Aquino, 2016). Unsustainability is the result of the mode of transformation present in the traditional economic process of the market economy, which consists of the transformation of low-entropy energy and matter (natural resources), transforming them into high-entropy energy (degradation), energy that becomes unusable. The increase in the productive activity of this process will cause environmental problems (Moutinho; Robaina; Macedo, 2018).

These resources extracted by economic activity are taken from the environment without considering its finiteness. Extraction worsens as economies and their productive activities develop. Consequently, more developed economies tend to consume more energy and matter as needed. Therefore, according to the hegemonic pattern of some countries about others, the matter and energy used by developed countries come from countries that export raw materials, an export that occurs based on repeated excesses of the natural resources of these exporting countries (Maldonado, 2018).

Thus, these so-called more developed economies pollute the planet more and at the same time generate an irreparable debt to underdeveloped countries and to the planet. The occurrence of environmental damage is irreversible, which means that economic growth is achieved at the expense of potential benefits for future generations (Maldonado, 2018; Cavalcanti, 2004; Oliveira, 2017).

According to Winckler and Renk (2017), for Georgescu-Roegen, human beings produce utilities from available matter and energy, so it is necessary to consider the economic process starting from the physical point of view, in which what enters the process is equivalent to valuable natural resources, and what is discarded is expressed in worthless waste. Thus, according to the authors, energy presents itself in two qualitatively distinct states, the free available energy being usable, and the imprisoned energy being unusable. The first form of energy represents balance, while the second represents chaos and disorder, entropy.

In short, EE aims at the sustainable use of the environment, is based on transdisciplinary studies, and highlights the social issues and the deterioration and transformation of ecological environments (Oliveira, 2017). The neoclassical (traditional) economy reduces spending and produces waste, and during the process of transforming natural resources into goods and services they propose to provide well-being to society through consumption; however, this process also generates malaise represented by deterioration (Maldonado, 2018).

Therefore, there is an incoherence between the current model of economic growth perpetuated with the neoclassical perspective, based on the uninterrupted environmental degradation that is evident, whether due to climate change, an increase in the ozone layer hole, or an increase in environmental and health problems resulting from the incorrect disposal of solid waste in the environment. This economic growth, which does not consider the limits of regeneration of the environment and the limits of support of the disorder imposed on it, is a risk to the maintenance of life since unsustainable consumption and production patterns are impracticable on a finite planet (Coletti; de Aquino, 2016; Efing;Geromino, 2016).

The uninterrupted search for economic growth, increased productivity and profit maximization have had a direct impact on the process of regeneration of natural resources in the environment, causing the possible depletion of non-renewable resources, since they will be unable to replenish themselves naturally due to their excessive use, thus creating an unsustainable cycle of production and consumption (Efing;Geromino, 2016). Therefore, it is advocated to reduce the negative impacts that this growth causes on the environment through the examination of production and consumption modes (Coletti; Aquino, 2016).

2.2 The Second Law of Thermodynamics: Entropy of the Economic System

Given the above, the economic process has an entropic nature since economic activity, by using conserved energy of low entropy, decreases the useful capacity of this energy to produce work. Because of this, the second law of thermodynamics, the law of entropy, is used to relate economic evolution and the thermodynamic process, given that every productive process (including the economic one) results in changes in the environment, in the transformation of matter and energy (Raine, Foster, Potts, 2006; Coletti; Aquino, 2016; Thampipallai, 2016; Cavalcanti, 2018).

The entropy process is a physical concept addressed by EE, bioeconomy, and econophysics, and refers to the transformation of energy within a thermodynamic system, a system expressed on the planet Earth and its ecosystems, to which the economy belongs, since each economic activity necessarily needs natural resources (natural capital) available in nature, for goods and services to be produced (Silveira, 2015; Rosser, 2016; Melgar-Melgar; Hall, 2020).

Given this, the environment will only be able to absorb a certain amount of energy, the unabsorbed energy results in degradation (Cavalcanti, 2015; Barbosa; Marques, 2015). Therefore, as the Earth is an isolated system, the available energy tends to decrease, and the unavailable energy tends to increase. Thermodynamics, therefore, imposes a limit on the unsustainable growth of the economy, since this economy is not capable of developing without the use of natural resources (Georgescu-Roegen, 1986).

If the economy were a closed and isolated system, it could fully develop if it fully consumed all the waste generated in the production process, ensuring perfect sustainability, which is unpassable (Barbosa; Marques, 2015). There is, therefore, an interdependence between the economy and the environment, where the use of natural capital (R) is constant to achieve higher levels of production (Y) (Thampapillai, 2016).

Authors such as Kovalev (2016) argue there is a mistake in relating economics and thermodynamics because, according to him, the Earth is not a closed system. It is in constant transformation and energy flow with the sun and outer space, and these are low-entropy energy sources that keep the Earth in constant balance, thus avoiding a lack of entropy control. In this way, the influence that the economy and its mode of production impose on global entropy is small.

However, for Lizarazo (2018), Cechin and Veiga (2010) the Earth is finite and economic growth conceived in an unlimited way is contrary to the principles of the 2nd law of thermodynamics, hence the relationship of this concept with the economy, the Earth is a closed system, so its amount of energy does not change even receiving energy from the sun.

Thus, the use of the laws of thermodynamics is relevant to understanding the complexity of economic systems and their relationships with the ecosystems in which they operate, within local, physical, and chemical constraints. Both systems (economic and ecosystem) are related and co-evolve, and their relationship arises as an economy's wealth is measured in consumption and consumption causes degradation and high environmental costs (Lizarazo, 2018).

This transformation of energy and matter, as well as the generation of waste, occurs faster than nature can transform this waste into more resources. Just as energy and low-entropy matter are the inputs used by economic activity in the production of products and services, high-entropy waste is the product of this process (Cechin; Veiga, 2010). Still, the waste generated is often unusable, as recycling is not the complete solution for the conservation of natural resources, because no matter how advanced the recycling processes are, it will never be 100% functional, and losses and waste are inevitable (Winckler; Renk, 2017).

Given this, Gonçalves (2016) argues that the increase in waste generation relates to economic growth and the increase in the consumption capacity of low-income social classes, as well as new consumption habits increasing consumption by industrialized, disposable products, and the planned obsolescence of products (Ribeiro, 2018). In underdeveloped countries, pollution is associated with poverty and population growth, these countries exert more pressure on natural resources, contributing to their degradation because they do not have technologies as advanced and environmentally sustainable as developed countries (Rodrigues, 2016;Menuzzi; Silva, 2015). Being the result of unsustainable patterns of production and consumption at a global level, such patterns need to be reviewed to ensure better living conditions for future generations (Inoue; Ribeiro, 2016).

The generation of waste is inevitable given the way all of humanity works, as it is up to human beings to develop ways to minimize the amount of waste produced, its treatment, and environmentally appropriate final disposal (Conde, 2014). To this end, in Brazil, the National Solid Waste Policy (PNRS) Law No. 12,305/2010 was enacted in Brazil, in which solid waste is defined as "all material, object, discarded resulting from human activities in society", unbridled exploitation of natural resources, intensified consumption, aggravates the amount of Urban Solid Waste (USW) that is improperly dumped into the environment (Cardoso, 2015).

That said, the increase in the generation of this waste, and its inadequate final disposal in the environment or open dumps, can affect public health through the contamination of diseases often spread by vectors, harm social welfare, soil contamination, pollution of water resources by leached waste that flows into rivers and/or watersheds, air pollution through the decomposition of organic matter, aggravation of global warming by the production of methane gas, factors that represent environmental degradation (Conde, 2014; Gomes, 2017).

As previously mentioned, human intervention can minimize the degree of disorder that this waste causes in the ecosystem, reducing ecological impacts, reducing the generation of this waste, investing in recycling, reverse logistics, and reinsertion of waste into the production cycle, among others (Brandino; Serpa; Oliveira, 2016; Silva; Alves, 2014). Society's consumption and production patterns need review, giving preference to cleaner production processes, and consumption of biodegradable products, in addition to minimizing the consumption of non-renewable energy by opting for other forms of energy generation with fewer negative impacts on the environment.

Thus, entropy proposes a limitation (rational use) of the plundering of natural resources, not encouraging the abolition of capitalism or the extermination of economic growth, but a growth that respects the biophysical and chemical limits of the ecosystem.

3 Methodology

This study is based on mixed methodologies (Tashakkori; Teddlie, 2003; Tashakkori; Johnson; Teddlie, 2021), which involves qualitative and quantitative approaches, and integrates statistical and thematic data analysis. This methodology wasfocused on analyzing the correlation of waste generation with the growth of the economy using GDP as the main reference and its environmental degradation by high entropy exposed by the second law of thermodynamics. By combining qualitative and quantitative methods, this study aims to broaden and deepen the understanding of the proposed theme and corroborate the results found (Gil, 2019). Data collected from 2012 to 2019, using Pearson's correlation coefficient.

The Pearson coefficient is used to measure two variables that are linearly related. The Pearson coefficient takes values between -1 and 1, where 1 (r=1) indicates a positive correlation between the variables, and -1 (r=-1) indicates a negative correlation between the variables. In this sense, the Pearson coefficient was used in the correlation between USW and GDP. In interpreting the values of the Pearson coefficient, the correlation scale of Hoffman (2016) was used. The GDP data were obtained from ABRELPE and IBGE.

The approach to the problem was quantitative, employing statistical methods to correlate the increase in the generation of urban solid waste with the increase in GDP, representing the growth of the economy. From this analysis, two hypotheses were proposed to be evaluated based on the results found. The quantitative approach allows for the formulation of hypotheses, their acceptance or refutation, and utilizes data collection and statistical analysis to prove theories (Lakatos;Marconi, 2017).

4 Results and Discussion

According to Onoue and Ribeiro (2016), there is a relationship between Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth and the amount of USW generated. This relationship tends to be higher in low- and middle-income countries that seek economic advancement, compared to fully developed countries. High-income countries have been more successful in separating wealth production from USW generation. Therefore, the increase in a nation's wealth production is measured by the evolution of GDP.

However, because GDP is a quantitative measurement, it does not cover factors that would demonstrate the development of a nation, such as quality of life, life expectancy, level of education, and health conditions. Thus, focusing solely on quantitative growth can directly harm the quality of environment (Efing;Geromino, 2016). GDP represents the total value of goods and services produced in a nation, state, or municipality each year (IBGE, 2020). This study utilized the annual GDP value of Brazil from 2012 to 2019, expressed in trillions of Brazilian reais.

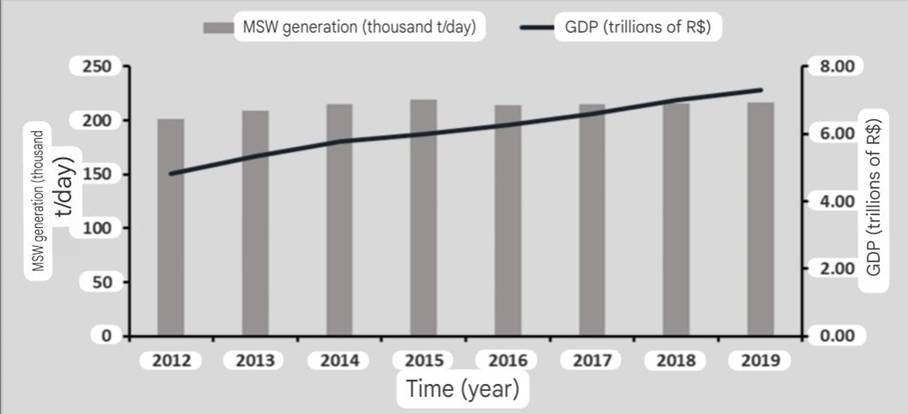

Figure 1: Data on USW generation t/day and GDP in trillions, in the 2012-2019 interval.

Source: Adapted from ABRELPE and IBGE.

Figure 1 shows the amount of USW generation and GDP in millions during the analyzed period. From the graph there is a constant increase in the value of GDP over the years, although this increase is more pronounced than the increase in the generation of USW per day. The latter also showed an increase from 2012 to 2015, but in 2016 there was a decrease of 0.04% in the daily generation of USW compared to the previous year.

From the second quarter of 2014 to mid-2015, the Brazilian economy faced a recession, resulting in a drop in economic activity during the period. This is also reflected in the slight increase in real GDP from 2014 to 2015. In 2015, the GDP growth rate reached 3.5%. From 2016 onwards, the Brazilian economy began to recover but still operated at a negative rate of -3.3%. This was influenced by economic factors such as the significant drop in Fixed Capital Formation (GFCF and political factors like the impeachment of the president in August 2016 (Oreiro, 2017; IBGE 2020).

During this recession, there was also an impact on the daily generation of USW, as a recession leads to a decrease in consumption and economic activity. For example, in 2015, the daily generation of USW was approximately 219 thousand tons/day, which decreased to around 214 thousand tons/day in 2016.

According to Melgar-Melgar and Hall (2020), GDP is linked to the consumption of matter and energy, which are essential for wealth production, hence the use of thermodynamic concepts in economic activity.Data from ABRELPE (2012; 2020) shows a significant increase in the daily generation of USW in Brazil from 2014 to 2015, influenced by factors like increased purchasing power, income, cultural habits, events, population growth, among others. The average USW generation during the analyzed period was 213.23 thousand tons per day, while the average GDP was R$ 6.13 trillion per year. Despite varying proportions, the increase in USW generation correlates with GDP growth. Therefore, higher GDP leads to increased USW generation and the associated environmental, health, and social.

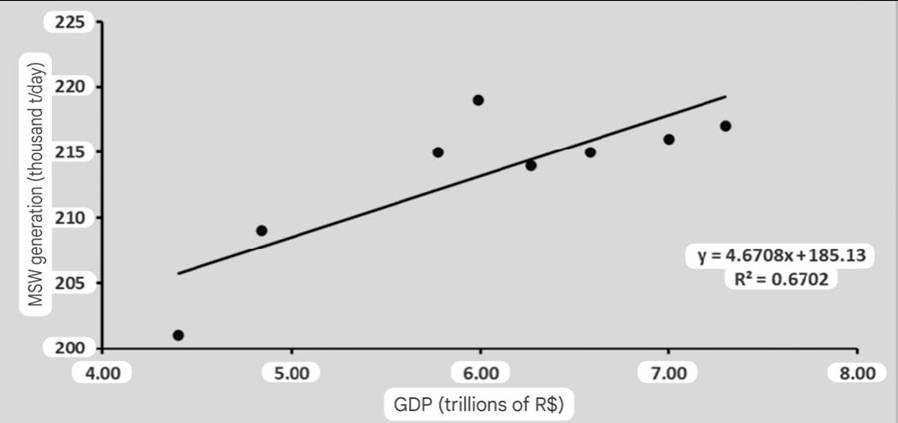

Based on Brandino, Serpa, and Oliveira (2016), waste generation produces entropy, negatively impacting the environment, and causing pollution. It is crucial for human actions to minimize these impacts. Statistical analysis yielded a p-value of 0.01 with a significance level of 95%, indicating a statistical significance between the variables. This supports the null hypothesis that there is a positive correlation between Brazilian GDP growth and USW generation.

The Pearson correlation index (r=0.81) confirms a strong positive correlation between Brazilian GDP and USW generation. This aligns with Campos' (2012) assertion that GDP significantly influences USW generation. This finding highlights the threat to the ecosystem and potential consequences for future generations due to the unsustainable extraction of natural resources and inadequate waste disposal methods.

Figure 2: Scatter Diagram.

Source: Prepared by the authors (2020).

According toFigure 2, we can see a positive correlation between the variables generation of USW and GDP. It is evident that the increase in USW generation is constant, while there is a peak in GDP growth. Later this value falls and grows again in a moderate way. It is possible to assume that with the growth of the economy, there is also an increase in the purchasing power of the population, as well as an evolution of income and an increase in consumerism.

The daily life of society tends to consume more industrialized, disposable products, which contributes to the increase in the generation of waste. Not to mention the culture of obsolescence, in which the industry is innovating more in new products, even if they are not significantly different from each other. Marketing and advertisements stimulate the population to purchase these products.

The economy can and must grow if this growth is conscious and sustainable. It is necessary to ensure that future generations can enjoy the same natural resources that we enjoy today, and in the same quantity. This will only be possible once the dominant conception of the economy over the environment changes, where environmental damage is still taken for granted. To achieve this, the economy and the environment need to be treated co-evolutionarily, respecting natural limits and moving towards a better life in the social, environmental, and economic sense. New ways of producing clean energy, biodegradable, sustainable products, and eco-friendly productions are actions that guarantee the continuation of the economic system while producing a positive impact on the environment.

Thus, Melgar-Melgar and Hall (2020) conclude that economic processes will generate high-entropy waste, given that the economic process functioning will always use low-entropy energy and matter, and this entropic process is unaccounted for by the neoclassical model of economics. Therefore, it is necessary to replace the view of environmental economics with an ecological economy.

From the neoclassical point of view, environmental expenses and damage are considered external to production; however, someone pays for them, which is society. Society pays for these "externalities " that economic activity causes in the form of decreased quality of life, changes in global temperature, degradation, and loss of biodiversity, as well as problems inherent to the generation of USW.

It is advocated to incentivize economic growth capable of relating the economy and social well-being together, minimizing stress on the ecosystem, producing only what it is capable of absorbing, and accepting the fact that the economic system operates within a larger open system.

Growth in compliance with the limits imposed by the natural ecosystem, respecting the conscious supply of natural resources, and the control of USW dumping into the environment. The relationship between the economy and the environment is complex, and this relationship generates environmental damage. Since the action of human beings is harming the maintenance of life on the planet, it is crucial to reverse the growth model imposed by orthodox economics and establish a new form of sustainable development respecting the laws of the ecosystem.

As previously mentioned, regarding the two hypotheses initially proposed, H0 and H1, it is intended to accept the H0 hypothesis that there is a direct correlation between the growth of the Brazilian GDP and the generation of USW.

The secondary data indicated in Table 1 were obtained from the Panoramas published by the Brazilian Association of Public Cleaning and Special Waste Companies (ABRELPE) in the period from 2012 to 2019, and the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) with GDP values during the mentioned period. This information was subjected to the estimation of Pearson's coefficient (r) using descriptive statistics and linear correlation, a test performed using the Minitab computer program version 18.1.0.

Pearson's coefficient assumes values from -1 to 1, with (r=1) indicating a positive perfect correlation between the variables, meaning that both increase exponentially and (r= -1) indicating a negative perfect correlation between the variables, i.e., while one variable increases, the other decreases. To interpret Pearson's value, Hoffman's (2016) correlation intensity scale was used, and a 95% confidence level (a=0.05) was adopted.

Table 1: USW generation data t/day and GDP in trillions.

|

Year |

USW generation (thousand tons/day) |

GDP (trillions R$) |

|

2012 |

201.058 |

4.403 |

|

2013 |

209.280 |

4.840 |

|

2014 |

215.297 |

5.778 |

|

2015 |

218.874 |

5.996 |

|

2016 |

214.405 |

6.267 |

|

2017 |

214.868 |

6.583 |

|

2018 |

216.629 |

7.000 |

|

2019 |

217.224 |

7.300 |

Source: Prepared by the authors of the paper adapted from ABRELPE and IBGE.

5 Final Remarks

The ideal economic model to discuss the biophysical limits of the Earth and the maintenance of human life is the Ecological Economics model, which considers quantitative and qualitative elements, as opposed to Neoclassical Economics which only discusses the market and resource allocation, in other words, a quantitative analysis.

Economic activity, therefore, generates a waste of natural resources that, together with the damage that the environment suffers from the excessive extraction of resources, should be considered in the economic system, and no longer treated as a mere externality.

It is necessary to assume nature as the limit to production processes, respecting its limits of waste absorption as well as the supply of non-renewable resources through new environmental legislation, programs to reduce energy consumption, and control of population growth, in addition to the adoption of new clean production and consumption processes that minimize global entropy.

Adopting a vision of interdependence between the economy and the environment is important to follow the transformations that the economic process and its incessant search for increased wealth, productivity, and environmental consequences undergo. Growth as it is accounted for is valid for measuring the wealth output of a nation, state, or region, but it is not and can not be a measure of total wealth. Since it is a quantitative measure, it does not address issues intrinsic to development, as well as the quality of life, quality of the environment, health, social inequality, extremely significant variables.

The rush to achieve GDP growth under the illusion that it will guarantee the wealth of a nation has caused irreparable damage to the environment and the quality of life of society. That said, this growth has become unsustainable because it does not promote the preservation of natural resources or pay attention to the reduction of waste dumping and damage caused by economic activity, based on the physical and chemical limits of nature, expressed by environmental degradation, climate change, problems that go beyond the borders of cities or countries. This growth has provided limits to its growth.

With orthodox economics leading the way in environmental policies that favor economic activity and disfavor the environment, it is leading the planet to a possible depletion of natural resources, where the pricing of natural resources, which additionally provide services strictly necessary for human life, is not enough to address the relationship between the economy and the environment.

As follows, EE promotes a review of this relationship between economy and environment, prioritizing an interdisciplinary, harmonious discussion, where the economy grows and develops within natural limits that allow the maintenance of human life in the long term, without harming access to natural resources for future generations. To this end, thermodynamics is approached to express the damage that the transformation of low-entropy energy into high-entropy energy causes on the planet.

For further research, the study of entropy and its relationship with environmental degradation is proposed, by other practical examples, such as the emission of Greenhouse Gases (GHG), its relationship with the productive activity of industrialized countries, and its plans for minimizing the pollution generated by them.

References

ABRELPE. Panorama dos Resíduos Sólidos no Brasil 2012. 28 p. Disponível em: < http://abrelpe.org.br/download-panorama-2012/>. Acesso: 28 jun. 2019

ABRELPE. Panorama dos Resíduos Sólidos no Brasil 2013. 28 p. Disponível em: < http://abrelpe.org.br/download-panorama-2013/>. Acesso: 28 jun. 2019

ABRELPE. Panorama dos Resíduos Sólidos no Brasil 2015. 19 p. Disponível em: < http://abrelpe.org.br/download-panorama-2015/>. Acesso: 28 jun. 2019

ABRELPE. Panorama dos Resíduos Sólidos no Brasil 2016. 15 p. Disponível em: < http://abrelpe.org.br/download-panorama-2016/>. Acesso: 28 jun. 2019

ABRELPE. Panorama dos Resíduos Sólidos no Brasil 2017. 15 p. Disponível em: < http://abrelpe.org.br/download-panorama-2017/>. Acesso: 28 jun. 2019

ABRELPE. Panorama dos Resíduos Sólidos no Brasil 2018-2019. 15 p. Disponível em: < https://abrelpe.org.br/download-panorama-2018-2019/>. Acesso: 28 jun. 2019

ABRELPE. Panorama dos Resíduos Sólidos no Brasil 2020. 15 p. Disponível em: < https://abrelpe.org.br/panorama-2020/ />. Acesso: 05 jan. 2021

BARBOSA, L. C. A.; MARQUES, C. A. Sustentabilidade ambiental e postulados termodinâmicos à luz da obra de Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen. Revista Eletrônica em Gestão, Educação e Tecnologia Ambiental, v. 19, n. 2, p. 1124-1132, 2015.

BRANDIE, A. P.; BARLETTE, V. E. Degradação ambiental: uma abordagem por entropia. DisciplinarumScientia| Naturais e Tecnológicas, v. 2, n. 1, p. 161-170, 2001.

BRANDINO, H.; SERPA, N.; OLIVEIRA, C. H. Gerenciamento e Destinação de Resíduos da Construção Civil nas Cidades Brasileiras. CALIBRE-Revista Brasiliense de Engenharia e Física Aplicada, v. 1, n. 1, p. 5-11, 2016.

CAMPOS, H. K. Tavares. Renda e evolução da geração per capita de resíduos sólidos no Brasil. Engenharia Sanitária e Ambiental, v. 17, n. 2, p. 171-180, 2012.

CARDOSO, M. A., et al. O despejo de resíduos sólidos nas ocupações irregulares no Canal do Jandiá (Macapá-AP). Revista Nacional de Gerenciamento de Cidades, v. 3, n. 19, p.149-161, 2015.

CAVALCANTI, C. Economia ecológica: uma possível referência para o desenho de sistemas humanos realmente sustentáveis. Redes, v. 22, n. 2, p. 56-69, 2017.

_____________, C. Pensamento socioambiental e a economia ecológica: nova perspectiva para pensar a sociedade. Desenvolvimento e Meio Ambiente, v. 35, p. 169-178,2015.

_____________, C. De laEconomía Convencional a laEconomía Ecológica: el significado de Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen y la Encíclica LaudatoSi'del Papa Francisco. Gestión y ambiente, v. 21, n. 1supl, p. 49-56, 2018.

_____________, C. Uma tentativa de caracterização da economia ecológica. Ambiente & Sociedade, v. 7, n. 1, p. 149-156, 2004.

CECHIN, A. D.; VEIGA, J. E. A economia ecológica e evolucionária de Georgescu-Roegen. BrazilianJournalofPoliticalEconomy, v. 30, n. 3, p. 438-454, 2010.

CONDE, T. T.; STACHIW, R.; FERREIA, E. Aterro sanitário como alternativa para a preservação ambiental. Revista Brasileira de Ciências da Amazônia, v. 3, n. 1, p. 69-80, 2014.

EFING, A. C.; GEROMINI, F. P. Crise ecológica e sociedade de consumo. Revista Direito Ambiental e Sociedade, v. 6, n. 2, p. 225-238, 2016.

GEORGESCU-ROEGEN, N. The entropylawandtheeconomicprocess in retrospect.Eastern Economic Journal, v. 12, n.1, p. 3-25. 1986

GIL, A. C. Métodos e técnicas de pesquisa social. Editora Atlas SA, 2019.

GLUCINA, M. D.; MAYUMI, K. Connecting thermodynamics and economics: Well‐lit roads and burned bridges. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, v. 1185, n. 1, p. 11-29, 2010.

GOMES, N. A., et al. Diagnóstico ambiental qualitativo no lixão da cidade de Pombal, Paraíba. Revista Verde de Agroecologia e Desenvolvimento Sustentável, v. 12, n. 1, p.61-67, 2017.

GONÇALVES, M. D. A. et al. Um estudo comparado entre a realidade brasileira e portuguesa sobre a gestão dos Resíduos Sólidos Urbanos. Sociedade & Natureza, v. 28, n. 1, p. 9-20, 2016.

HOFFMANN, R. Estatística para economistas. São Paulo: Cengage Learning,2016.

IBGE. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Produto Interno Bruto – PIB. .< http://www.ipeadata.gov.br/exibeserie.aspx?serid=38415>. Acesso em: 19 de novembro de 2020.

IBGE. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Agência de sala de imprensa – PIB. </ https://agenciadenoticias.ibge.gov.br/agencia-sala-de-imprensa.html>. Acesso em 04 de janeiro de 2021.

INOUE, C. Y. A.; RIBEIRO, T. M. M. L. Padrões sustentáveis de produção e consumo: resíduos sólidos e os desafios de governança do global ao local. Meridiano 47-Boletim de Análise de Conjuntura em Relações Internacionais, v. 17, p. 1-19, 2016.

KOVALEV, A. V. Misuse of thermodynamic entropy in economics. Energy, v. 100, p. 129-136, 2016.

LAKATOS, E. M.; MARCONI, M. A. Metodologia científica. São Paulo: Atlas, 2017.

MALDONADO, F. E. C. Renta negativa y decrecimiento económico. Apuntesdel CENES, v. 37, n. 65, p. 53-74, 2018.

MALTHUS, T. R. An essay on the principle of population. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992.

MILL, J. S.Principles of political economy. New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1885.

MOUTINHO, V.; ROBAINA, M.; MACEDO, P. Economic-environmental efficiency of European agriculture– a generalized maximum entropy approach. AgriculturalEconomics, v. 64, n. 10, p. 423-435, 2018.

MENUZZI, T. S.; SILVA, L. G. Z. Interação entre economia e meio ambiente: uma discussão teórica. Electronic Journal of Management, Education and Environmental Technology (REGET), v. 19, p. 9-17, 2015.

MELGAR-MELGAR, R. E.; HALL, C. A. Why ecological economics needs to return to its roots: the biophysical foundation of socio-economic systems. EcologicalEconomics, v. 169, p. 1-14, 2020.

MONTIBELLER, G.; SOUZA, G. C.; BÔLLA, K. D. S. Economia ecológica e sustentabilidade socioambiental. Revista Brasileira de Ciências Ambientais, v. 23, p. 25-35, 2012.

OLIVEIRA, E. Economia verde, economia ecológica e economia ambiental: uma revisão. Revista Meio Ambiente e Sustentabilidade, v. 13, n. 6, 2017.

OREIRO, J. L. A grande recessão brasileira: diagnóstico e uma agenda de política econômica. Estudos Avançados, v. 31, n. 89, p. 75-88, 2017.

PARETO, V. Manual ofpoliticaleconomy. Variorum edition. Edited by Aldo Montesano, Alberto Zanni, Luigino Bruni, John S. Chipman and Michael McLure. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014 [1906, 1909].

RAINE, A.; FOSTER, J.; POTTS, J. The new entropy law and the economic process. Ecologicalcomplexity, v. 3, n. 4, p. 354-360, 2006.

RIBEIRO, B. M. G.; MENDES, C. A. B. Avaliação de parâmetros na estimativa da geração de resíduos sólidos urbanos. Revista Brasileira de Planejamento e Desenvolvimento, v. 7, n. 3, p. 422-443, 2018.

RIFKIN, J.; HOWARD, T. Entropylaw: a new world view. New York: The Viking Press, 1980.

RODRIGUES, L. dos A., et al. Pobreza, crescimento econômico e degradação ambiental no meio urbano brasileiro. Revibec: revista de laRed Iberoamericana de Economia Ecológica, v. 26, p.11-24, 2016.

ROSSER, J. B. Entropy and econophysics. The European Physical Journal Special Topics, v. 225, n. 17-18, p. 3091-3104, 2016.

SILVA, J. G.; ALVES, J. L. Desfazendo a entropia por meio da logística reversa. RDE-Revista de Desenvolvimento Econômico, v. 16, n. 30, p.120-133, 2014.

SILVEIRA, A. D. Ensaio (IN) Sustentabilidade Ambiental: Fundamentos Epistemológicos. Revista Competitividade e Sustentabilidade, v. 2, n. 1, p. 102-109, 2015.

SPEROTTO, F. Q. Externalidades, ganhos de escala e de escopo. In: CONCEIÇÃO, C. S. FEIX, R. D. (Org.). Elementos conceituais e referências teóricas para o estudo de Aglomerações Produtivas Locais. Porto Alegre: FEE, 2014. p. 32-44.

TASHAKKORI, A.; JOHNSON, R. B.; TEDDLIE, C. Foundations of mixed methods research: integrating quantitative and qualitative approaches in the social and behavioral sciences. London, SAGE Publications, 2021.

TASHAKKORI, A.; TEDDLIE, C. Handbook of mixed methods in social sciences and behavioral research. Thousand Oaks, CA, SAGE, 2003.

THAMPAPILLAI, D. J. Ezra Mishan's cost of economic growth: Evidence from the entropy of environmental capital. The Singapore Economic Review, v. 61, n.3, p.1-10, 2016.

WINCKLER, S.; RENK, A. GEORGESCU-ROEGEN, Nicholas. O decrescimento. Entropia. Ecologia. Economia. Apresentação e organização Jacques Grinevald e Ivo Rens; tradução Maria José Perillo Isaac. São Paulo: Editora Senac São Paulo, 2012. (Tradução a partir da edição francesa La décroissance: entropie, écologie, économie, da editora Sang de la Terre, de 2008). Revista Catarinense de Economia, v. 1, n. 1, p.211-218, 2017.

ZANIRATO, S. H.; ROTONDARO, T. Consumo, um dos dilemas da sustentabilidade. Estudos Avançados, v. 30, n. 88, p. 77-92, 2016.