Sustainable Management and Treatment of Explosive Solid Waste: Approaches for Civil and Military Applications

Alvaro Luiz Mathias[2]

Energetic materials release their chemical energy through slower exothermic reactions, as observed in propellants, or instantaneously, as with explosives. This narrative review provides a comprehensive and holistic perspective on the complex lifecycle of explosive solid waste (E-SW) and related energetic materials. It covers key aspects such as explosive waste research, definition, classification, history, applications, management complexities, environmental and health impacts, disposal methods, and green innovations. While explosives are critical in both civil and military applications, they pose significant environmental and health risks throughout their lifecycle. E-SW management remains an urgent yet underexplored area in scientific literature, especially compared to other explosive-related topics. Traditional disposal methods, like open burning and detonation, result in significant pollution, contaminating soil, water, and air. Despite this, these methods persist due to the lack of safer, economically viable alternatives. Innovative solutions such as biological treatments show promise in mitigating environmental damage, particularly in decontaminating metal residues for recycling. However, challenges in scalability and effectiveness remain. Prioritizing the development of biodegradable energetic materials and designing devices with safer dismantling procedures are essential. The pursuit of green innovations and further research is crucial to refining E-SW management strategies, reducing pollution, and protecting ecosystems and human health.

Keywords: Energetic Substances; Explosives Management; Contamination; Waste; Treatment.

Gestão Sustentável e Tratamento de Resíduos Sólidos Explosivos: Abordagens para Aplicações Civis e Militares

Resumo

Materiais energéticos liberam sua energia química tanto por meio de reações exotérmicas mais lentas, como nos propelentes, quanto de maneira quase instantânea, como ocorre nos explosivos. Esta revisão narrativa busca oferecer uma visão abrangente e holística sobre o ciclo de vida complexo dos resíduos explosivos (E-SW) e de outros materiais energéticos, abordando aspectos fundamentais como pesquisa de resíduos explosivos, definição, classificação, histórico, aplicações, complexidades de gestão, impactos ambientais e à saúde, métodos de descarte e inovações verdes. Embora essenciais em aplicações civis e militares, os explosivos apresentam sérios riscos ambientais e à saúde ao longo de sua vida útil. O gerenciamento de E-SW permanece uma questão crítica, mas ainda pouco explorada na literatura científica em comparação com outros tópicos relacionados a explosivos. As práticas de descarte tradicionais, como a queima e detonação a céu aberto, geram poluição significativa, contaminando o solo, a água e o ar. No entanto, esses métodos continuam a ser amplamente utilizados devido à falta de alternativas seguras e economicamente viáveis. Soluções inovadoras, como o tratamento biológico, mostram-se promissoras na mitigação de danos ambientais, especialmente na descontaminação de resíduos metálicos para reciclagem. Contudo, há desafios consideráveis na escalabilidade e eficácia desses métodos. O desenvolvimento de materiais energéticos biodegradáveis e dispositivos projetados com procedimentos de desmontagem mais seguros deve ser uma prioridade. A busca por inovações verdes e por mais pesquisas é fundamental para refinar as estratégias de gerenciamento de E-SW, reduzindo a poluição e protegendo tanto os ecossistemas quanto a saúde humana.

Palavras-chave: Substâncias Energéticas; Resíduos Energéticos; Contaminação; Resíduo; Tratamento.

Recebido em: 02/09/2024

Aceito em: 20/10/2024

Publicado em: 25/07/2025

1 Introduction

First, it is essential to clarify two key terms that are fundamental to this narrative review. The term energetic material is broader than explosive material because it encompasses any substance capable of storing chemical energy that is released through exothermic reactions (heat-producing reactions). Explosive materials, on the other hand, are a specific subset of energetic materials. While all explosives are energetic, not all energetic materials are explosive. For instance, propellants are energetic materials that release energy in a controlled, gradual manner, unlike explosives, which release energy rapidly and violently. This distinction is crucial for understanding the management and applications of these substances, especially in contexts such as military, industrial, and environmental safety.

Managing explosive solid waste (E-SW) and other energetic materials is a critical but often overlooked environmental and safety challenge. Both military and civilian applications of energetic materials contribute to widespread soil, water, and air contamination, presenting long-term risks to ecosystems and human health. From lead pollution in military firing ranges to the harmful effects of explosives like trinitrotoluene (TNT) and hexahydro-1,3,5-trinitro-1,3,5-triazine (RDX), these substances pose challenges not only in terms of their immediate destructive capacity but also their lingering toxicity. Despite advancements in technology and regulatory frameworks, research on E-SW remains limited, particularly regarding its broader environmental impacts. By addressing these challenges and highlighting knowledge gaps, this study emphasizes the urgent need for sustainable solutions in E-SW management, providing a narrative review that underscores the importance of refining legal and technological approaches.

The sustainable management of E-SW, especially from civil and military applications, remains underdeveloped. This immaturity is linked to the materials’ complexity, a lack of stringent legal frameworks, technological deficiencies in waste treatment, limited research, and the absence of global consensus on managing such waste. Consequently, energetic materials have contaminated soils worldwide through manufacturing processes, military conflicts, and training exercises (Jenkins et al., 2006; Pichtel, 2012; Duttine; Hottentot, 2013; Mystrioti; Papassiopi, 2024).

Civil and military activities involving these materials have caused substantial air, water, and soil pollution due to their intricate mix of organic and inorganic components. Specific activities like shooting ranges, mechanized military drills, and wartime environments introduce hazardous elements such as arsenic (As), cadmium (Cd), copper (Cu), mercury (Hg), manganese (Mn), lead (Pb), antimony (Sb) and zinc (Zn) into the environment, presenting serious risks related to poisoning and bioaccumulation (Rodríguez-Seijo et al., 2024).

While lead contamination, particularly linked to recreational hunting, has received more attention (Di Minin et al., 2021), significant research gapsstill exist (Rodríguez-Seijo et al., 2024).For example, the concentration of Pb in South Korean military firing zones is reported to be 6.6 times higher than the established safety threshold of 700 mg Pb/kg (Ahmad et al., 2012). Lead contamination has been documented in larger organisms like mammals, birds, and plants, but its effects on micro- and mesofauna, aside from earthworms, remain poorly studied (Rodríguez-Seijo et al., 2024). Furthermore, explosiveorganic compounds such as TNT and RDX also contribute to environmental pollution(Rodríguez-Seijo et al., 2024).

By the early 20th century, more thansixty energetic materials were developed, primarily for military, civilian, or dual-use purposes (Bernstein; Ronen, 2011). These substances, when triggered, either deflagrate or explode due to rapid decomposition, emitting not only significant heat and harmless gases but also toxic emissions like volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and fine particulates(Agrawal; Hodgson, 2019; Kalderis et al., 2011). While the immediate destruction caused by explosives is well-documented, the longer-term chronic toxicity—particularly their diffusion in ecosystems, including marine environments—is often overlooked (Rodríguez-Seijo et al., 2024; Akhavan, 2011).

Even the recycling of metallic fractions of these devices presents contamination risks to soil and groundwater (Kalderis et al., 2011; Mystrioti; Papassiopi, 2024). While the use of explosives is widely associated with military applications, their presence in civilian contexts such assport shooting, hunting (Di Minin et al., 2021), mining (Zawadzka-Małota, 2015), and construction (Stark; Asce, 2010) is underestimated. In these settings, attention is focused on preventing damage from projectiles or rock fragments, neglecting the environmental toxicity of components such as flame retardants and heavy metals in their containers (Pichtel, 2012). Additionally, the risk of exposure to toxic gases in indoor and outdoor environments is a serious occupational hazard, potentially leading to long-term illnesses or fatal incidents (Zawadzka-Małota, 2015; Mallon et al., 2019). This danger can be mitigated by using explosives with a balanced oxygen content. However, in military scenarios, the unpredictability of explosive remnants of war (ERW) and unexploded ordnance (UXO) complicates the management of these hazards long after conflicts have ended (Duijm; Markert, 2002; Gichd,2014).

Energetic materials and their by-products form a distinct category of solid waste, referred to as "explosive solid waste" (E-SW) in this study. This term encompasses waste materials that are prone to flammability, reactivity, or both (USEPA, 2019). A comprehensive approach to managing E-SW must consider the entire life cycle of these materials, from the development of "green" devices to responsible disposal methods (Talawar et al., 2009). This includes optimizing production processes, minimizing usage, preventing abandonment, and employing proper treatment and recycling techniques (Wilkinson; Watt, 2006). Moreover, mitigating soil contamination in usage areas and prohibiting outdated disposal methods, such as launching waste into the sea—a practice that persisted until the 1990s (IMO, 2024)—are vital steps forward.

Military activities across regions like the United States, Europe, and Asia (Akhavan, 2011; Pichtel, 2012), along with civil industries such as mining (Zawadzka-Małota, 2015) and building demolitions (Stark; Asce, 2010), underscore the increasing need for efficient E-SW (Explosive Solid Waste) management. This growing demand highlights the critical importance of implementing effective strategies to mitigate the environmental and health impacts associated with the disposal and treatment of explosive materials.Considering this, the present study conducts a narrative reviewof the management of explosive waste, offering insights into current trends, challenges, and knowledge gaps within this domain.

2 Methodology

This narrative review applied a structured methodology to ensure comprehensive and replicable research findings. The following steps describe the approach used:

2.1. Search Strategy and Keywords

The ScienceDirect database served as the platform for a systematic search(https://www.sciencedirect.com/) from 2001 to July 25, 2024. The relevance and the depth of scientific studies were evaluated using the following search terms:

ü explosive

ü energetic

ü explosives management

ü energetics management

ü explosive residue

ü explosive residue management

ü contamination by explosives

ü explosives treatment

These terms were input individually and in combination into the "Find articles with these terms" field on the ScienceDirect platform to capture a wide range of relevant publications. For the selected period (2001 to 2025), the total and partial search results were classified according to the "types of articles available on ScienceDirect" (i.e., "review articles," "research articles," "book chapters," and "book reviews"). These categories, deemed most significant for scientific dissemination, were used to calculate the percentage contribution of each type. Additionally, the evolution of certain terms was evaluated over time, from 2001 to 2025.

2.2 Selection Criteria

Articles were initially filtered by title and keywords to determine their relevance to the objectives of this narrative review. Abstracts of the shortlisted articles were then reviewed to refine the selection further, ensuring the content was related to the key topics of explosive solid waste management, environmental impacts, and treatment technologies.

2.3 Additional Sources

Filtering articles by title and keywords helped evaluate their relevance to the objectives of this narrative review, such as Google Scholar, PubMed, SpringerLink, etc. Cross-referencing the bibliographies of key studies also helped identify further critical sources.

2.4 Data Analysis and Integration

The selected articles underwent a thorough analysis, focusing on the methodologies, results, and conclusions regarding explosive waste management. These data were synthesized to develop a holistic understanding that aligns with the study's goals, addressing the complexities of explosive waste management and mitigation strategies.

3 Discussion

This article aims to inspire sustainable management practices for organic and inorganic explosive wastes and their complementary components. To address the challenges in explosive waste management, a holistic approach is crucial—one that not only evaluates environmental and health impacts but also integrates a comprehensive understanding of key areas that will be illustrated: research on explosive/energetic materials management (3.1), definition (3.2), classification (3.3), history (3.4), applications (3.5), complexity of management (3.6), harmful impacts (3.7), destination methods (3.8) and green innovations (3.9). This includes advanced treatment and disposal techniques and strategies for reducing explosive waste at the source. By emphasizing both innovative treatment and initiative-taking waste minimization, this review advocates for a lifecycle management strategy that reduces risks while fostering sustainable solutions.

3.1 Current trends and gaps in explosive waste management research

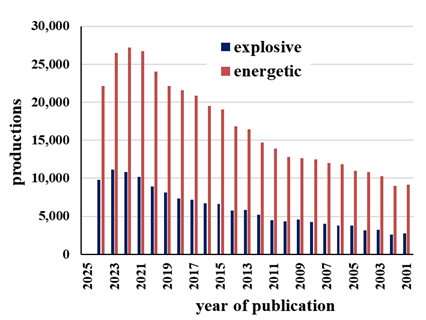

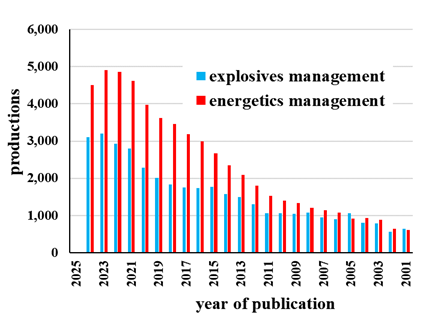

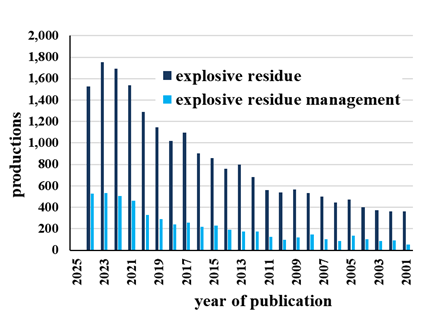

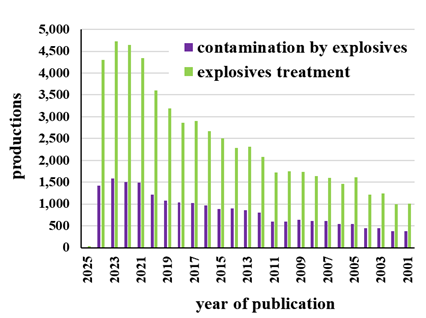

Research in explosive waste management has shown consistent growth, especially as we approach 2025. However, significant gaps remain. The descriptor "energetic" is frequently used interchangeably with "explosive," which introduces complications in filtering relevant research. While "energetic" covers a wide array of references across different fields, the term "explosive" is more targeted, particularly for studies related to military and civil construction applications (Figure 1a). Despite this, when paired with "management," the distinction between the two becomes less critical (Figure 1b).

Figure 1: Evolution of publications on explosive solid waste based on relevant keywords.

a b

c d

Source: The Authors.

Current research on explosive waste management and contamination remains underexplored compared to the broader field of treatment methodologies (Figure 1c, 1d). Although there is a growing body of literature on waste management, most publications are concentrated on book chapters (33.41%), research articles (32.8%), and review articles (17.10%), underscoring a lack of comprehensive, standalone books on the subject (0.40%). This imbalance reveals a gap in detailed field data, which hampers further progress in developing effective waste management solutions. As a result, there is an increasing demand for more dedicated studies in this domain.

Thus, performing this narrative review, given the higher quantity of book chapters and other review literature, allows for a holistic, integrative approach to analyzing the topic of solid waste management. It balances the breadth of existing sources while still providing room for identifying areas that need further exploration, without the need for a stringent, systematic methodology. The trends and data in this narrative review emphasize the critical need for continued research to fill these gaps and foster more robust practices for explosive waste management.

To generate this narrative review, in addition to 10 publications from Elsevier (24.39%), the study draws from a diverse range of sources, including other scientific publishers, government bodies, legal instruments, and technical organizations. These include 2 from Springer (4.88%), 2 publications from John Wiley & Sons (4.88%), 1 from the Royal Society of Chemistry (2.44%), and 1 from CRC Press (2.44%). Additionally, 3 publications from MDPI (7.32%) and 1 from the Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining (2.44%) were utilized.

Further contributions come from Oxford University Press (1 publication, 2.44%), Pyrotechnica Publications (1, 2.44%), American Society of Civil Engineers (1, 2.44%), Cambridge University Press (1, 2.44%), and the Instituto Militar de Engenharia (IME) (1, 2.44%). Relevant input also comes from industrial and technical entities such as Dyno Nobel (1, 2.44%), Dynasafe (1, 2.44%), and the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) (1, 2.44%).

Moreover, the study includes 3 publications from the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) (7.32%), 1 military-focused publication from the US Government (2.44%), 1 from the World Health Organization (2.44%), and 1 from the United Nations (2.44%). Lastly, 4 legal publications covering Brazilian and Portuguese legislation (9.76%) round out the study’s multidisciplinary approach.

3.2Definition of energetic materials

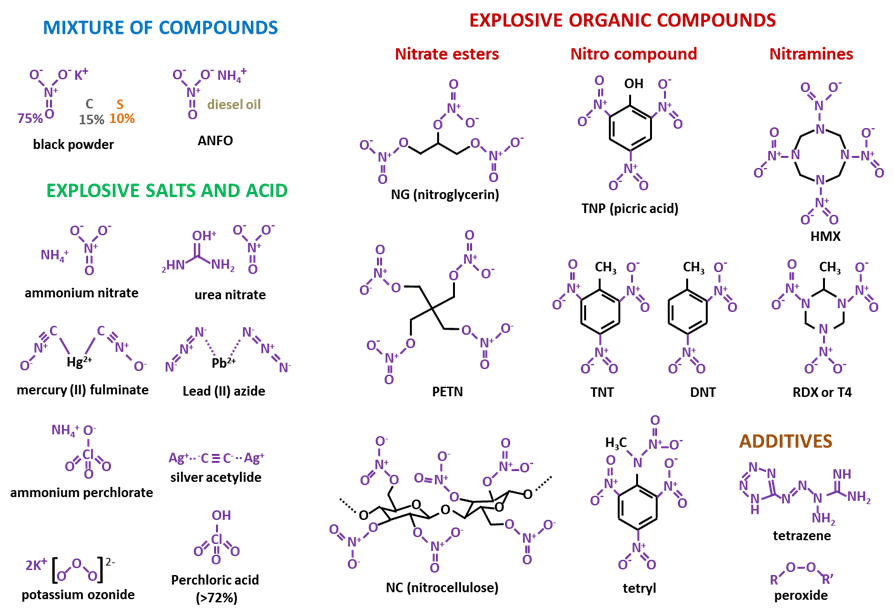

Figure 2:Chemical classes of energetic materials with civil and military use.

Source: The Authors. Adapted from Sućeska (1995);Akhavan (2011) and Pichtel, 2012.

Energetic materials are designed to maximize energy output (HE, Table 1) and create rapid gaseous expansion (VEG) at high velocities (DV), in this case being the explosive subgroup. These characteristics are influenced by the oxygen balance (OB), which measures the excess or deficiency of oxygen relative to what is required for complete combustion. A positive oxygen balance, common in highly explosive materials like nitroglycerin, indicates a surplus of oxygen, which increases handling risks. The risk is higher when the material has a low deflagration temperature (DT), allowing it to ignite more easily. Additionally, explosive reactions may generate particulate matter and release metals from the material's composition, such as mercury from fulminates or metal casings. The pressure wave from the gaseous expansion can also produce intense sound waves(Meyer; Köhler; Homburg, 2007; Chatterjee et al., 2017).

Table 1:Detonation velocity (DV), oxygen balance (OB), heat of explosion (HE, formation of H2Oliq), volume of explosion gases (VEG) and deflagration temperature (DT) of explosive energetic substances (S) or mixtures (M)*1.

|

Explosive |

|

DV, m/s |

OB, % |

HE, kJ/kg |

VEG, l/kg |

DT, oC |

Type |

|

Ammonium Nitrate |

|

n.r. |

20.0 |

2,479 |

980 |

210 |

S |

|

Ammonium perchlorate |

|

6,300*2 |

34.0 |

1,972 |

799 |

350 |

S |

|

Ammonium Picrate |

|

7,150 |

-52.0 |

2,871 |

909 |

320 |

S |

|

ANFO |

|

3,500 |

n.r. |

3940- |

n.r. |

n.r. |

M |

|

Carbon |

|

n.r. |

-266.7 |

–13,942 |

n.r. |

n.r. |

S |

|

Sulfur |

|

n.r. |

-100.0 |

n.r. |

n.r. |

n.r. |

S |

|

HMX (octagen) |

|

9,100 |

-21.6 |

6,197 |

902 |

287 |

S |

|

Lead azide |

|

4,900 |

-5.5 |

1,638 |

231 |

340 |

S |

|

Mercury Fulminate |

|

4,250*2 |

-11.2 |

1,735 |

n.r. |

165 |

S |

|

Nitrocellulose 13,3% |

|

4,409 |

-28.7 |

4,312 |

871 |

n.r. |

S |

|

Nitroglycerin |

|

7,600 |

3.5 |

6,671 |

716 |

n.r. |

S |

|

Pentolite |

|

7,400 |

n.r. |

n.r. |

n.r. |

n.r. |

M |

|

PETN |

|

8,400 |

-10.1 |

6,322 |

780 |

202 |

S |

|

Picric acid |

|

7,350 |

-45.4 |

n.r. |

826 |

300 |

S |

|

Potassium nitrate |

|

n.r. |

39.6 |

6,004 |

n.r. |

n.r. |

S |

|

RDX (hexogen) |

|

8,750 |

-21.6 |

6,322 |

903 |

n.r. |

S |

|

Silver acetylide |

|

acetylide |

-26.7 |

n.r. |

n.r. |

273 |

S |

|

Tetrazene |

|

n.r. |

-59.5 |

n.r. |

n.r. |

140 |

S |

|

Tetryl |

|

7,570 |

-47.4 |

4,773 |

n.r. |

185 |

S |

|

TNT |

|

6,900 |

-73.9 |

1,090 |

n.r. |

300 |

S |

|

Urea Nitrate |

|

4,700*2 |

-6.5 |

3,211 |

n.r. |

186 |

S |

Source: The Authors. *Adapted from Meyer; Köhler; Homburg, 2007;*2 Table of explosive detonation velocities (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Table_of_explosive_detonation_velocities); n.r. = not reported.

Table 1 presents key properties of various energetic substances and mixtures, including detonation velocity (DV), oxygen balance (OB), heat of explosion (HE), volume of explosion gases (VEG), and deflagration temperature (DT), which are critical to understanding the behavior and risks associated with each material. The development and application of energetic materials, particularly those with military and civil uses, are inherent to their chemical composition, energy release capacity, and environmental impact. As the field advances, innovations in greener, safer materials remain a priority, emphasizing the balance between performance and safety. Understanding the properties of energetic materials allows for improved risk management in their handling and disposal processes, while also facilitating the development of more sustainable and less hazardous alternatives.

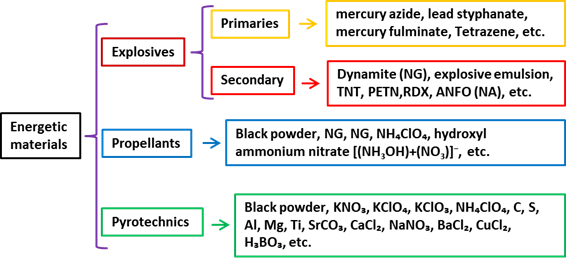

3.3Classifications of energetic materials

Energetic materials can be categorized according to various criteria and properties. Based on reaction speed, they range from terribly slow (m/s) to instantaneous (km/s). This behavior is referred to as deflagration when occurring below the speed of sound in air (with a detonation velocity around 310-350 m/s), and detonation when between 1,500 and 9,000 m/s (Meyer; Köhler; Homburg, 2007; Conkling; Mocella, 2018).This wide range has enabled the development of propellants, pyrotechnics, and explosives (Figure 3) for both civilian and military applications(Akhavan, 2011). Such complexities present significant challenges in managing Explosive Solid Waste (E-SW), making it difficult to identify both imminent hazards and persistent pollutants, which will be further discussed.

Figure 3: Proposal for classification of energetic materials and devices with examples for E-SW management.

Source: The Authors. Adapted from Sućeska (1995) and Akhavan (2011).

Propellants typically contain a stoichiometric amount of endogenous oxygen (Table 1, OB). Although stable, they can detonate under certain conditions, as seen in black powder formulations (Sućeska, 1995; Akhavan, 2011). These materials provide thrust in engines and function as deflagrators to initiate other explosives. For example, fireworks propellant may consist of about 75% potassium nitrate, 15% charcoal, and 10% sulfur (Shimizu, 1996; Mallon et al., 2019). Potassium nitrate serves as an endogenous oxygen source, supporting combustion.

Pyrotechnic explosives are solidscomposed of fuel and oxidizing agents, capable of sustaining combustion without external air. They are designed to produce effects like heat, light, or smoke in applications such as fireworks and signaling devices(Valença, 2001; Charsley et al., 2003). Explosives, on the other hand, are substances or mixtures that detonate instantly when triggered, with widespread use in both civilian and military fields, thus playing a significant role in E-SW management (Meyer; Köhler; Homburg, 2007; HSE, 2014).

Chemical classification is complex, with no universally clear pattern except for endogenous oxygen availability.Energetic materials include those with slower combustion rates (like pyrotechnics) and those that detonate explosively. The range of materials spans from stable compounds, such as ammonium nitrate, to extremely sensitivesubstances like nitroglycerin. These classifications are further detailed by their physical and chemical characteristics(Akhavan, 2011; Chatterjee et al., 2017; Kramarczyk et al.,2022).

3.4History of the most popular explosives

Black powder, also known as gunpowder, was the first explosive ever described and initially used in civil pyrotechnic applications by Arab, Hindu, and Chinese cultures. Despite being a low explosive, it was widely utilized in civil engineering and military operations until it was superseded by higher nitrogen explosives such as nitrocellulose and nitroglycerin (Shimizu, 1996; Valença, 2001; Charsley et., 2003; Akhavan, 2011).

In the early 19th century, nitrocellulose was identified as the first high explosive, but its early instability limited its practical use until Henri Braconnot improved its viability by combining nitric acid with wood fibers or starch. Similarly, nitroglycerin (NG) was synthesized in 1847 by Ascanio Sobrero (Wisniak, 2006), but due to its initial instability, it was not widely adopted until Alfred Nobel stabilized it in 1867 by incorporating absorbent materials, leading to the invention of dynamite. Nobel’s innovations, including dynamitegelatin and explosive gelatin, expanded the applications of these materials, especially in civil uses where safety and production efficiency were prioritized (Shimizu, 1996; Valença, 2001; Akhavan, 2011).

Ammonium nitrate (NA), synthesized in 1659 by Glauber, does not explode by itself but is a rich oxygen source, making it useful in high-explosive mixtures such as ANFO (Ammonium Nitrate/Fuel Oil). While early ANFO use was limited by its hygroscopic properties, the development of explosive emulsions and muds improved its versatility (DYNO, 2024). Current research is focused on enhancing the performance, safety, and environmental impact of these emulsion explosives, including minimizing emissions like carbon monoxide and nitrogen oxides (Zawadzka-Małota, 2015; Kramarczyk et al., 2022).

Later in the 19th century, picric acid gained prominence in military applications, although its instability and corrosive properties led to its replacement by trinitrotoluene (TNT), which became the standard explosive by 1914 (Shimizu, 1996; Valença, 2001; Akhavan, 2011). During World War II, the demand for high explosives led to the mass production of pentaerythritol tetranitrate (PETN) and RDX (cyclonite), the latter of which was used in some of the most powerful explosives developed for the war, such as HMX and the Torpex mixture (Akhavan, 2011; Chatterjee et al., 2017).

3.5Current use of explosives for civil and military purposes

Explosives are extensively applied in both civil and military sectors. In civil construction, explosives like nitroglycerin gel (NG) or dynamite (NG mixed with diatoms or clay) are used for rock dismantling in mining, tunnel excavation, road construction, and quarrying. ANFO, a solid blend of ammonium nitrate and fuel (typically diesel), is favored due to its cost-effectiveness and performance. Additionally, explosive emulsions, stable oxidant-fuel mixtures dispersed in an aqueous matrix, are used for rock blasting by being pumped into drilled holes. Perchlorate-based explosives are also prevalent because of their high stability and explosive potential. These civil operations require highly trained personnel and adherence to strict safety protocols (Meyer; Köhler; Homburg, 2007; Akhavan, 2011; Stark; Asce, 2010; DYNO, 2024).

To enhance safety and efficiency, various software tools, such as JKSimBlast and LS-DYNA, assist in the calculation and simulation of explosive needs for specific tasks like rock blasting or demolition (Meyer; Köhler; Homburg, 2007; Stark; Asce, 2010).

In the military domain, explosives are crucial in ordnance and demolition. Commonly used materials include TNT, DNT, RDX, HMX, C-4, Semtex, and nitroglycerin. TNT is favored for its stability and destructive power, making it ideal for ammunition and demolition charges. RDX and HMX are widely used in warheads, bombs, and explosive mixtures due to their high energy output. Plastic explosives like C-4 and Semtex, which blend RDX with other materials such as PETN, are valued for their malleability, stability, and ease of use in demolition and explosive device neutralization (Meyer; Köhler; Homburg, 2007; Mallon et al., 2019). PETN, known for its sensitivity to heat and shock, finds use in detonators and as an additive in other explosives to boost power. Specialized explosives like tetryl are used in certain military applications (Meyer; Köhler; Homburg, 2007; USEPA, 2019).

3.6Complexities of explosive solid waste (E-SW) management

The management of explosive solid waste (E-SW) presents significant complexities, involving multiple stages such as transportation, pre-treatment, downsizing, processing (treatment, recycling), and final disposal (Duijm; Markert, 2002; Wilkinson; Watt, 2006). This process becomes more challenging when dealing with unexploded ordnance (UXO) and explosive remnants of war (ERW), which include landmines and other abandoned ordnance as defined by Protocol V of the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons (CCW). These remnants continue to pose serious risks in conflict-affected regions like Afghanistan, Cambodia, Colombia, Myanmar, Pakistan, and South Sudan (Duttine; Hottentot, 2013).

Beyond the immediate threat to human life, the improper management of E-SW can result in long-term environmental damage. Contamination of soil, water sources, and air from the toxic components of explosives is a persistent issue, posing chronic risks to ecosystems, animals, and human health (Pichtel, 2012; Mallon et al., 2019; Mystrioti; Papassiopi, 2024). The extraction and handling of UXO, particularly in combat situations, add further complexity due to the risk of accidental detonation, which endangers both medical staff and patients when UXO is found embedded in casualties (Oh et al., 2018).

Effective management, therefore, requires not only the safe handling of explosive waste but also strategies for mitigating environmental contamination and ensuring public safety in affected regions.

3.7Environmental and Health Risks of Explosive Waste

Explosives, particularly those containing nitro (–NO₂) and nitrate (–ONO₂) groups, detonate by releasing harmless byproducts like water vapor, CO₂, and N₂. However, incomplete combustion can produce toxic gases, including nitrous oxides (NO and NO₂), which are particularly hazardous in enclosed spaces, such as excavation sites, putting operators at risk (Stark; Asce, 2010). Severalcontaminated sites, especially in the USA, Europe, and Asia, have been polluted by substances like RDX and HMX due to military activity and improper disposal practices (Kalderis et al., 2011). These pollutants pose serious risks to both humans and animals, with TNT and RDX linked to liver damage and seizures (EPA, 2014; EPA, 2017). Additionally, open burning or detonation further contributes to environmental degradation by releasing CO, unburned hydrocarbons, and nitrogen oxides, which contaminate soils and groundwater (USEPA, 2019; Mystrioti; Papassiopi, 2024).

Remediation of these contaminated sites is complex and hindered by the lack of effective mitigation technologies. However, innovative methods like using eggshells to stabilize lead in polluted soils show promise (Ahmad et al., 2012). Biodegradation through microorganisms, such as bacteria and fungi, is another emerging solution, but this method remains limited and requires further research (Bernstein; Ronen, 2011; Pichtel, 2012; Mystrioti; Papassiopi, 2024).

3.8Challenges in Explosive Waste Disposal: Methods, Regulations, and Environmental Impact

The generation of explosive solid waste (E-SW) primarily occurs during production, commercialization, and use, but poor management of obsolete artifacts also contributes significantly (Duijm; Markert, 2002). Historically, sea disposal was a customary practice following major world conflicts to avoid the logistical costs and risks of returning devices to their origins, alongside fears of misuse by adversaries. However, this practice was harshly criticized at the 1972 Stockholm Conference on the Environment due to concerns over marine pollution, supported by the United Nations General Assembly (UNITED NATIONS, 2017). This led to the progressive elimination of sea disposal, which was officially banned by a 1993 amendment, effective from 1994 (Wilkinson; Watt, 2006; USA, 2017; IMO, 2024).

Open burning (OB) and controlled open detonation (OD) have since become prevalent methods for E-SW disposal due to their simplicity, low cost, and perceived safety (Akhavan, 2011; USEPA, 2019). Despite the environmental drawbacks, including harmful air emissions, noise pollution, and contamination of soil and groundwater, these techniques are tolerated (Wilkinson; Watt, 2006). They are used for the destruction of explosives, propellants, and pyrotechnics in military munitions and various devices such as marine rockets, flares, fireworks, and airbags (Mallon et al., 2019; USEPA, 2019). While these methods continue to be practiced in Western Europe and the USA, growing pressure from environmental bodies, particularly in countries like Germany, the Netherlands, and Canada, calls for their eventual ban (Wilkinson; Watt, 2006).

The environmental impacts of OB and OD are considerable. These methods release toxic air pollutants, leave behind uncontrolled E-SW deposition, and occupy large land areas. While air and water pollution on global and regional scales are major concerns, the most severe effects are local. To mitigate these impacts, technologies such as closed detonation (CD), fluidized bed combustion (FBC), rotary kiln incineration (RK), and mobile kiln incineration (MF) have been developed. These technologies help contain waste and reduce land contamination, yet their implementation and costs remain significant challenges. The disposal of residual E-SW per unit mass differs between technologies: OB (0.36 kg/kg), OD (0.13 kg/kg), CD and MF (0.05 kg/kg), FBC (0.027 kg/kg), and RK (0.02 kg/kg). The land area required for operations follows a similar descending order: OB and OD require vast safety zones of 3,200,000 m², while RK, CD, FBC, and MF require much less land. Furthermore, the impact on gas emissions, particularly nitrogen oxides (NOx), varies across technologies, with OB being the most harmful (285 g/kg) andCDthe least (14 g/kg) (Duijm; Markert, 2002).Emissions control mechanisms,such as ammonia or urea injection to reduce NOx, add additional costs to these treatments(Oommen; Jain, 1999).

Transportation impacts also differ based on the proximity of E-SW generation sites to treatment facilities, with significant risks associated with transport (Duijm; Markert, 2002). While OB and OD remain the preferred methods, further studies comparing these technologies are essential to determine the best approaches for specific types of explosive waste. Additionally, the risk of handling explosives can be minimized by converting them into stabilized aqueous sludges during early elimination phases. Though labor-intensive, CD with flue gas cleaning is a preferred alternative for small ammunition (e.g., fuses, mines, pyrotechnics), but it requires highly specialized personnel (Duijm; Markert, 2002; USEPA, 2019).

High-pressure water jets and FBC provide safer alternatives to OB and OD, offering efficient incineration of desensitized ammunition in RK and MF systems. Although transport and traffic emissions are concerns, these risks are less severe than those associated with OB and OD (Duijm; Markert, 2002; USEPA, 2019). It is crucial to carefully design centralized or decentralized treatment installations, balancing environmental and safety considerations.

Legislation governing explosive waste disposal varies by country. In Portugal, Decree-Law No. 139/2002 allows for waste disposal through combustion, detonation, or chemical treatment in small fractions (PORTUGAL, 2002). In the UK, the Explosives Regulations 2014—SI 2014/1638—mandate safe disposal, including bioremediation under the Clean Air (Emission of Dark Smoke) Act (Wilkinson; Watt, 2006; HSE, 2014). Brazilian law assigns responsibility for explosive material control to the Armed Forces (BRASIL, 2019), and although it does not detail specificwaste treatments, the National Solid Waste Policy (PNRS) prohibits open burning in unlicensed facilities (BRASIL, 2010). US regulations (40 CFR § 265.382) prohibit open burning for hazardous waste, except for explosive waste, which must be destroyed at Department of Defense facilities (USA, 2024). Unfortunately, these areas often suffer from contamination (Jenkins et al., 2006).

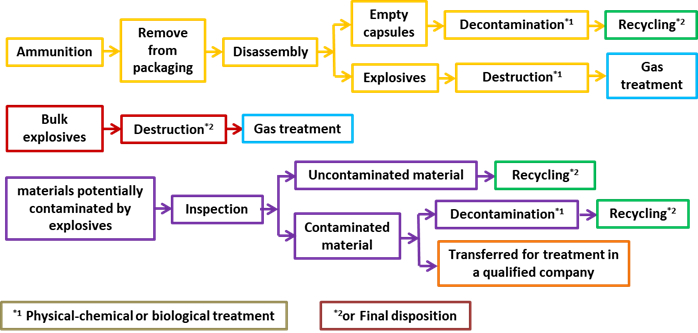

The USEPA(2019) proposed a process to minimize contamination, including dismantling ammunition, applying thermal and chemical destruction, and recycling decontaminated metal parts. Although thermal destruction with gas treatment is recommended, certain shock-sensitive ammunition still lacks more sophisticated solutions and is a new business opportunity (Heaton, 2018).Additionally, priority should be given to recycling materials and reducing harmful emissions as much as possible, with any remaining waste being disposed of in specialized landfills (Wilkinson; Watt, 2006). To support this approach, a process flow diagram was developed, drawing on insights from numerous studies to illustrate best practices for the management and disposal of explosive waste (Figure 4)

Figure 4: Flowchart of the dismantling and destruction process of military devices.

Source: The Authors. Adapted from Duijm and Markert (2002), Wilkinson and Watt (2006), Kalderis et al., 2011,Pichtel (2012) and USEPA, 2019).

There is no global consensus on E-SW treatment due to the variety of explosives and devices. However, emerging trends favor processes that minimize pollution and gaseous emissions, highlighting the need for innovative technologies throughout the entire lifecycle of explosive products. Bioprocessing plays a pivotal role in soil decontamination (Mystrioti; Papassiopi, 2024; Wilkinson; Watt, 2006) and can facilitate metal recycling from dismantled devices. Biodegradation of energetic materials, such as TNT and RDX, offers an economical alternative to conventional methods like soil excavation or in situ physicochemical treatments(Mystrioti; Papassiopi, 2024). Composting and phytoremediation are preferred for sites with high concentrations of organic explosives (Kalderis et al., 2011). Bioremediation and phytoremediation hold significant promise for treating explosives like TNT, RDX, and HMX, though biotreatment remains sensitive to environmental conditions and must be closely monitored (Chatterjee et al., 2017; Kalderis et al., 2011; Wilkinson; Watt, 2006).

3.9Innovations in green energetic materials: reducing environmental impact in military operations

The most effective strategy for managing explosive waste is to prevent its generation, aligning with principles outlined in policies like Brazil's National Solid Waste Policy (PNRS) (BRASIL, 2010). In response, several countries are investing in the development of "green" energetic materials that aim to minimize environmental damage in military applications. For instance, ammonium nitrate is increasingly being used as a chlorine-free propellant instead of ammonium perchlorate, reducing harmful emissions(Oommen; Jain, 1999). Metal-free primary explosives are also being explored to lessen environmental risks (Sabatini; Oyler, 2016).

Despite these advancements, green energetic materials currently pose significant cost challenges, with some formulations being up to 100 times more expensive than conventional explosives (Talawar et al., 2009). Continued research is critical to overcoming this hurdle, focusing on improving performance, synthetic utility, and cost efficiency while minimizing environmental impact (Sabatini; Oyler, 2016).

Innovative approaches, such as embedding Bacillus subtilis GN spores into explosives like ethylene glycol dinitrate, allow for natural degradation in the soil after detonation, further reducing the environmental footprint (Dario et al., 2010). These developments underscore the importance of integrating environmental protection into the design and manufacture of military explosives, with global initiatives encouraging greener alternatives (Kalderis et al., 2011).

As military forces continue to adopt more sustainable technologies, green energetic materials hold the potential to revolutionize the field, balancing performance with environmental stewardship. However, further research and cost-reduction efforts are essential to make these materials viable on a large scale.

4 Conclusions

This narrative review offers a comprehensive and holistic overview of the current landscape in managing explosive solid waste (E-SW) and other related energetic materials. Covering crucial aspects such as the definition, classification, lifecycle, and environmental and health impacts of E-SW, this review highlights the complexities involved in handling and disposing of these hazardous materials. From unexploded ordnance (UXO) to explosive remnants of war (ERW), the challenges in managing E-SW are significant, necessitating specialized practices and strict regulatory compliance to minimize contamination and toxic exposure risks.

Traditional disposal methods, like open burning and detonation, remain prevalent but pose serious risks to both human health and ecosystems due to their contribution to soil, water, and air pollution. These methods continue to be used because safer, economically viable alternatives are lacking. However, emerging technologies such as fluidized bed combustion (FBC), closed detonation (CD), and microbial degradation, including the use of **Bacillus subtilis** GN spores, offer promising pathways toward more sustainable and less harmful waste management practices. These innovative approaches are vital for reducing environmental contamination, particularly in decontaminating metals for recycling.

Although the development of green energetic materials and sustainable methods presents higher upfront costs, they are necessary for long-term environmental protection and sustainability. The review emphasizes the urgent need for continued research and development in this area to make explosive waste treatment more efficient and environmentally friendly.

This review underscores the importance of advancing E-SW management strategies to align with global sustainability efforts, advocating for the development of biodegradable materials, safer dismantling procedures, and innovative technologies. Future research should focus on refining these solutions and fostering a multidisciplinary approach to ensure a more sustainable and safer future for explosive materials management.

5 Acknowledgements

We express our deep gratitude to CNPq, CAPES, DAAD, and UFPR for their essential financial and structural support in this research.

References

AHMAD, M.; HASHIMOTO, Y.; MOON, D. H.; LEE, S. S.; OK, Y. S. Immobilization of lead in a Korean military shooting range soil using eggshell waste: An integrated mechanistic approach. Journal of Hazardous Materials, v. 209-210, p. 392-401, 2012. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2012.01.047. Acesso em: 16 jul. 2024.

AKHAVAN, J. The Chemistry of Explosives. 3. ed. Cambridge: Royal Society of Chemistry, 2011.

AGRAWAL, J. P.; HODGSON, R. D. Organic Chemistry of Explosives. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, 2019. Disponível em: https://is.gd/WPVolz. Acesso em: 18 jul. 2024.

BERNSTEIN, A.; RONEN, Z. Biodegradation of the Explosives TNT, RDX and HMX. In: SHREE, N. S. (Ed.). Microbial Degradation of Xenobiotics. Environmental Science and Engineering. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2011. p. 135-176. Disponível em: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/226602004_Biodegradation_of_the_Explosives_TNT_RDX_and_HMX. Acesso em: 24 set. 2024.

BRASIL. Decreto n.º 10.030, de 30 de setembro de 2019. Aprova o Regulamento de Produtos Controlados. Diário Oficial da União: Brasília, 30 de set. de 2019. Disponível em: https://www.gov.br/defesa/pt-br/arquivos/File/legislacao/emcfa/2020/seprod/dec.10030.pdf. Acesso em: 24 jul. 2024.

CHARSLEY, E. L.; LAYE, P. G.; BROWN, M. E. Pyrotechnics. In: Handbook of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry. v. 2, Chapter 14, p. 777-815, 2003. Disponível em: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1573437403800183. Acesso em: 18 mar. 2024.

CHATTERJEE, S.; DEB, U.; DATTA, S.; WALTHER, C.; GUPTA, D. K. Common explosives (TNT, RDX, HMX) and their fate in the environment: Emphasizing bioremediation. Chemosphere, v. 184, p. 438-451, 2017. ISSN 0045-6535. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.06.008. Acesso em: 18 jul. 2024.

CONKLING, J. A.; MOCELLA, J. M. Chemistry of Pyrotechnics: Basic Principles and Theory. 3rd ed. Boca Raton: CRC Press, 2018. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1201/9780429262135. Acesso em: 16 jul. 2024.

DARIO, A.; SCHROEDER, M.; NYANHONGO, G. S.; ENGLMAYER, G.; GUEBITZ, G. M. Development of a biodegradable ethylene glycol dinitrate-based explosive. Journal of Hazardous Materials, v. 176, n. 1–3, p. 125-130, 2010. ISSN 0304-3894. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2009.11.006. Acesso em: 16 jul. 2024.

DI MININ, E.; CLEMENTS, H. S.; CORREIA, R. A.; CORTÉS-CAPANO, G.; FINK, C.; HAUKKA, A.; HAUSMANN, A.; KULKARNI, R.; BRADSHAW, C. J. A. Consequences of recreational hunting for biodiversity conservation and livelihoods. OneEarth, v. 4, p. 2021. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2021.01.014. Acesso em: 16 jul. 2024.

DYNO – Dyno Nobel. Practical Innovations: ANFO Explosive. Disponível em: https://www.dynonobel.com/practical-innovations/popular-products/anfo/. 2024. Acesso em: 24 jul. 2024.

DUIJM, N. J.; MARKERT, F. Assessment of technologies for disposing explosive waste. Journal of Hazardous Materials, v. 90, n. 2, p. 137-153, 2002. ISSN 0304-3894. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3894(01)00358-2. Acesso em: 20 jul. 2024.

DUTTINE, A.; HOTTENTOT, E. Landmines and explosive remnants of war: a health threat not to be ignored. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, v.91, n.3, 160 - 160A, 2013. Disponível em: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3590630/. Acesso em: 18 mar. 2024.

EPA. ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY. 2014. EUA. Technical Fact Sheet – 2,4,6-Trinitrotoluene (TNT), 8 p. Disponível em: https://19january2017snapshot.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2014-03/documents/ffrrofactsheet_contaminant_tnt_january2014_final.pdf >. Acesso em: 23jul. 2024.

EPA. ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY. 2017. EUA. Technical Fact Sheet – Hexahydro-1,3,5-trinitro1,3,5-triazine (RDX), 7 p. Disponível em: < https://19january2017snapshot.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2014-03/documents/ffrrofactsheet_contaminant_rdx_january2014_final.pdf >. Acesso em: 12 jul. 2024.

GICHD (Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining). A Guide to Mine Action. GICHD, 2014. Disponível em: https://www.gichd.org/publications-resources/publications/guide-to-mine-action-2014/. Acesso em: 18 jul. 2024.

HEATON, H. Is Open Burning/Open Detonation of explosives obsolete?. 2018. Disponível em: https://dynasafe.com/news-archive/open-burning-open-detonation-alternative/. Acesso em: 18 mar. 2024.

HSE. Health and Safety Executive. Explosives Regulations.2014 Disponível em: https://www.hse.gov.uk/explosives/new-regulations.htm. Acesso em: 15 jul. 2024.

IMO. International Marine Organization. Convention on the Prevention of Marine Pollution by Dumping of Wastes and Other Matter. Disponível em: https://www.imo.org/en/About/Conventions/Pages/Convention-on-the-Prevention-of-Marine-Pollution-by-Dumping-of-Wastes-and-Other-Matter.aspx. Acesso em: 16 jul. 2024.

JENKINS, T. F.; HEWITT, A. D.; GRANT, C. L.; THIBOUTOT, S.; AMPLEMAN, G.; WALSH, M. E.; RANNEY, T. A.; RAMSEY, C. A.; PALAZZO, A. J.; PENNINGTON, J. C. Identity and distribution of residues of energetic compounds at army live-fire training ranges. Chemosphere, v. 63, n. 8, p. 1280-1290, 2006. ISSN 0045-6535. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2005.09.066. Acesso em: 16 jul.2024.

KALDERIS, D.; JUHASZ, A. L.; BOOPATHY, R.; COMFORT, S. Soils contaminated with explosives: Environmental fate and evaluation of state-of-the-art remediation processes (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure and Applied Chemistry, v. 83, n. 7, p. 1407-1484, 2011. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1351/PAC-REP-10-01-05. Acesso em: 16 jul. 2024.

KRAMARCZYK, B.; SUDA, K.; KOWALIK, P.; SWIATEK, K.; JASZCZ, K.; JAROSZ, T. Emulsion Explosives: A Tutorial Review and Highlight of Recent Progress. Materials, v. 15, p. 4952, 2022. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15144952. Acesso em: 16 jul. 2024.

MALLON, T. M.; MATOS, P. G.; MONKS, W. S.; MIRZA, R. A.; BODEAU, D. T. Explosives and Propellants. In: Occupational Health and the Service Member. 2019. p. 561-592. Disponível em: https://medcoeckapwstorprd01.blob.core.usgovcloudapi.net/pfw-images/dbimagesOh%20ch%2028.pdf. Acesso em: 29 jul. 2024.

MEYER, R.; KÖHLER, J; HOMBURG, A. Explosive. 6th ed. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. 2007. Disponível em: https://miningandblasting.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/09/explosives-6th-edition-by-meyer-kohler-and-homburg-2007.pdf. Acesso em: 16 jul. 2024.

MYSTRIOTI, C.; PAPASSIOPI, N. A comprehensive review of remediation strategies for soil and groundwater contaminated with explosives. Sustainability, v. 16, p. 961, 2024. Disponível em:https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/16/3/961. Acesso em: 16 jul. 2024.

OH, J. S.; SEERY, J. M.; GRABO, D. J.; ERVIN, M. D.; WERTIN, T. M.; HAWKS, R. P.; BENOV, A.; STOCKINGER, Z. T. Unexploded Ordnance Management. Military Medicine, v. 183, n. 9/10, p. 24-28, 2018. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/usy064. Acesso em: 22 jul. 2024.

OOMMEN, C.; JAIN, S. R. Ammonium nitrate: a promising rocket propellant oxidizer. Journal of Hazardous Materials, v. A67, p. 253–281, 1999. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3894(99)00039-4. Acesso em: 16 jul. 2024

PICHTEL, J. Distribution and fate of military explosives and propellants in soil: a review. Applied and Environmental Soil Science, v. 2012, 617236, 2012. doi:10.1155/2012/617236. Disponível em: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1155/2012/617236. Acesso em: 18 jul. 2024.

PORTUGAL. Decreto-lei 139 de 17 de maio de 2002. Aprova o Regulamento de Segurança dos Estabelecimentos de Fabrico e de Armazenagem de Produtos Explosivos. Disponível em: https://dre.tretas.org/dre/152135/decreto-lei-139-2002-de-17-de-maio. Acesso em: 24 jul. 2024.

RODRÍGUEZ-SEIJO, A.; FERNÁNDEZ-CALVIÑO, D.; ARIAS-ESTÉVEZ, M.; ARENAS-LAGO, D. Effects of military training, warfare and civilian ammunition debris on the soil organisms: an ecotoxicological review. Biology and Fertility of Soils, 2024. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00374-024-01835-8. Acesso em: 16 jul. 2024.

SABATINI, J. J.; OYLER, K. D. Recent Advances in the Synthesis of High Explosive Materials. Crystals, v. 6, n. 1, p. 5, 2016. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst6010005. Acesso em: 16 jul. 2024.

SHIMIZU, T. Fireworks:The Art, Science, and Technique. 1st ed. Austin: Pyrotechnica Publications, 1996.

STARK, T. D; ASCE, P. E. F. Is Construction Blasting Still Abnormally Dangerous? Journal of Legal Affairs and Dispute Resolution in Engineering and Construction, v. 2, n. 4, 2010. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)LA.1943-4170.0000037. Acesso em: 16 jul. 2024.

SUĆESKA, M. Test methods for explosives. New York: Springer, 1995.

TALAWAR, M. B.; AGARWAL, A. P.; VISHWAKARMA, R. N.; MAHULIKAR, P. P. Environmentally compatible next generation green energetic materials (GEMs). Journal of Hazardous Materials, v. 161, n. 2-3, p. 589-607, 2009. Disponível em: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0304389408005335?via%3Dihub. Acesso em: 16 jul. 2024.

UNITED NATION. Solid Waste Disposal. In: The First Global Integrated Marine Assessment: World Ocean Assessment I. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017. p. 379-388. Chapter 24 - Solid Waste Disposal. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108186148. Acesso em: 18 jul. 2024.

USA - United States of America § 265.382 Thermal Treatment: Open burning; waste explosives.2024. Disponível em: https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-40/chapter-I/subchapter-I/part-265/subpart-P/section-265.382. Acesso em: 24 jul. 2024.

USEPA. United States Environmental Protection Agency's Report on “Hazardous Waste Permitting: Revisions to Standards for the Open Burning / Open Detonation of Waste Explosives”, EPA 530-R-19-007, 2019. Disponível em: https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2019-12/documents/final_obod_alttechreport_for_publication_dec2019_508_v2.pdf. Acesso em: 18 mar. 2024.

VALENÇA, U. S. Um pouco da história dos explosivos através de seus descobridores. Desenvolvimento e Tecnologia, v. 18, p. 43–62, 2001. Disponível em: https://rmct.ime.eb.br/arquivos/RMCT_1_quad_2001/hist_explo_descobrid.pdf. Acesso em: 16 jul. 2024.

ZAWADZKA-MAŁOTA, I. Testing of mining explosives with regard to the content of carbon oxides and nitrogen oxides in their detonation products. Journal of Sustainable Mining, v. 14, p. 173-178, 2015. Disponível em: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jsm.2015.12.003. Acesso em: 16 jul. 2024.

WILKINSON, J.; WATT, D. Review of demilitarisation and disposal techniques for munitions and related materials. Bruxelles: Munitions Safety Information Analysis Center, NATO Headquarters, 2006. Disponível em: https://www.rasrinitiative.org/pdfs/MSIAC-2006.pdf. Acesso em: 16 jul. 2024.

WISNIAK, J. Ascanio Sobrero. Revista CENIC Ciências Químicas, v. 37, nº 1, 41-47, 2006. Disponível em: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/236232939_Ascanio_Sobrero. Acesso em: 16 jul. 2024.